by Nancy Henry

This past March, twenty-seven people involved in U.S. horse racing, including trainers and veterinarians, were federally indicted for doping racehorses with banned substances. A New York Times article by Benjamin Weiser and Joe Drape reported: “To avoid detection of their scheme, the indictment said, the defendants routinely defrauded and misled federal and state regulators ‘and the betting public.’”

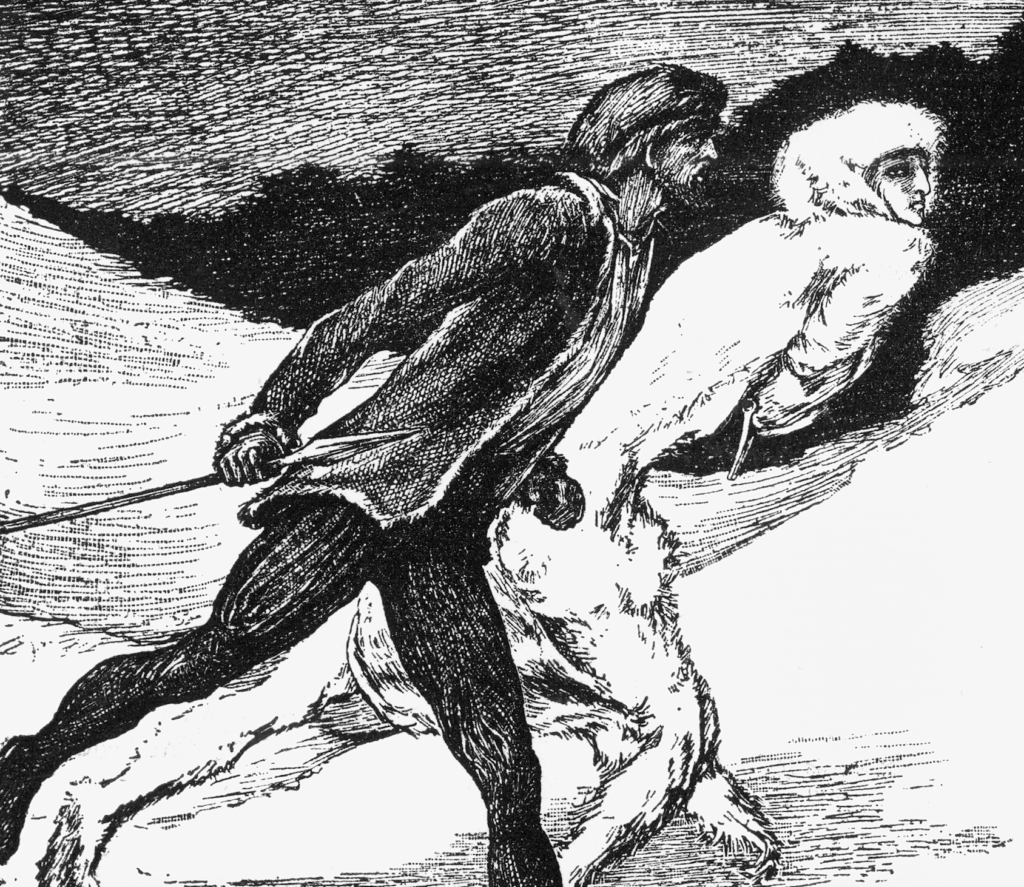

This ongoing case is part of a long, troubling history of horse-racing fraud. In Victorian Britain, attempts to cheat sometimes erupted into full-blown scandals. For example, the 1844 Epsom Derby was compromised by a series of deceits that included entering a four-year old as a three-year old. There are many ways to “fix” a race, but drugging or injuring the horse is particularly shocking because it involves a betrayal of trust, as well as physical harm. Fiction is uniquely able to create sympathy for the horse, and in some cases, imagine his thoughts. In Ouida’s Under Two Flags (1867), for example, the steeplechaser Forest King has his bit painted with poison, and we see the ensuing delirium through his eyes.

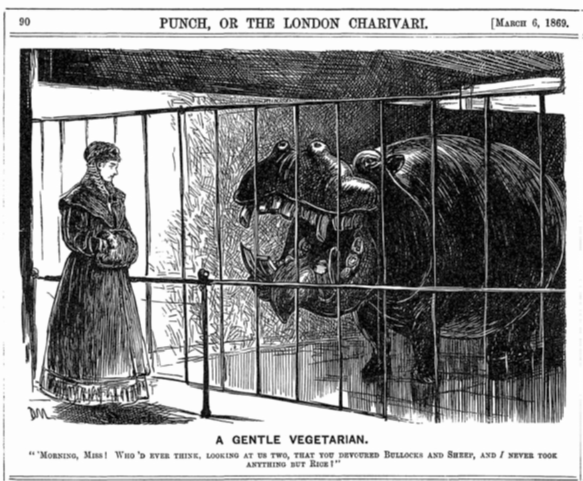

In Victorian fiction generally and racing fiction in particular, there is tension between the horse as a living, feeling creature and the horse as source of monetary value. Jane Smiley observes that in the eighteenth century, “horseracing, fiction, and capitalism came to form a mutually nurturing threesome” (44). In the nineteenth-century racing plots are also financial plots; horses are characters and commodities. Forest King’s loss results in financial ruin for his owner Bertie Cecil, and it redirects the novel’s plot. In Anthony Trollope’s The Duke’s Children (1880), Lord Silverbridge’s horse Prime Minister has a nail driven into his hoof on the morning of his race, causing Silverbridge to lose the tremendous sums he had bet on the horse.

In Charles Dickens’s The Old Curiosity Shop (1840-41), Little Nell attends the races, reflecting, “how strange it was that horses who were such fine honest creatures should seem to make vagabonds of all the men they drew about them” (157). Later novelists like George Moore in Esther Waters (1894) agreed. More recently, The Sport of Kings (2016) by C.E. Morgan explores the economic cultures of racing and breeding horses in Kentucky.

While many tracks closed temporarily, horse racing is one of the few sports that remained available for live viewing (and betting) in the US throughout the Covid-19 pandemic shut downs. For many gamblers, racing is entirely removed from the horses, who are represented by statistics in the racing form and numbers on a screen. Outrage over doping is apt to be more about financial loss than animal cruelty. Victorian literature is a good place to start when considering how horse racing, literary criticism and Animal Studies might intersect in order to bring attention to the harm done to horses when humans put money above the integrity of the sport and the safety of the horses.

This post forms part of a special issue on “Fraud and Forgery in Victorian Culture.” To read more see Nancy Henry, “Horse-Racing Fraud in Victorian Fiction.” Victorian Review, vol. 45, no. 2, Fall 2019, pp. 235-251.

Works Cited

Dickens, Charles. The Old Curiosity Shop. Ed. Elizabeth M. Brennan. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2008.

Smiley, Jane. “The Fiction of Horseracing.” Cambridge Companion to Horseracing, edited by Rebecca Cassidy. Cambridge UP, 2013, pp. 44–56.