by Christie L. Harner

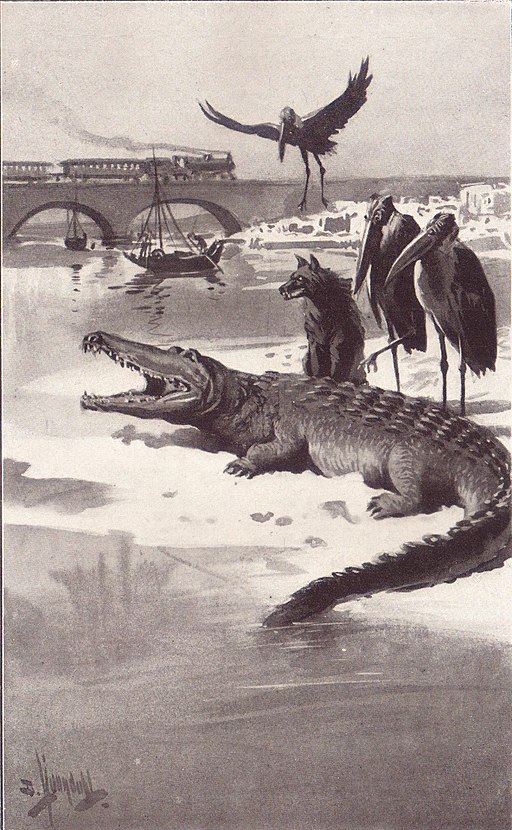

Mowgli grows up. He receives a jungle-appropriate education, experiences puberty and sexual attraction, and accepts a position as ranger in the Government Forest Service. Toomai, in the story that bears his name, also grows up – to be a renowned tracker in the imperial service – as does the “mutiny baby” who, as an adult, shoots and kills a legendary village crocodile. Outside the bounds of fiction, Robert Baden-Powell’s boy scouts grew up and into the militaristic roles for which they were trained: positions modeled, in the language of the scouts, on Rudyard Kipling’s stories.

The linear, progressive, and imperialist temporality of Kipling’s stories seems self-evident. Yet this reading has always troubled me. It is too determinist, prescriptive, and, above all, anthropocentric. It focuses too exclusively on the human characters in The Jungle Books and on what we might call “human” (unquestionably British) time. Even Jessica Straley’s wonderful reading, in her Evolution and Imagination in Victorian Children’s Literature, which probes the uneven temporalities of the stories and argues for a non-progressive teleology, attends only to Mowgli, to the exclusion of non-human species.

I began this article with a question: what other temporalities exist in Kipling’s stories, and how do those temporal scales and rhythms disrupt and reorient our reading practices? In turning attention away from the human, a multiplicity of temporal forms in The Jungle Books comes into focus: mating seasons, monsoon cycles, and diurnal and nocturnal behaviors. Moreover, given that in every story, the human presence has disrupted an existing ecosystem, Kipling’s collection also provides a series of case studies that depict the temporal instabilities of human-animal interactions. What the stories narrate is not so much “human time” as ecological regime shifts.

Drawing on the languages of political science and systems theory, the ecological term regime shift characterizes the irregular processes through which environmental states change. The phrase may invoke a tipping point, a temporal drag, or an adjustment to introduced time scales and rhythms. In my account, the term focuses our attention on the collisions of sociocultural time spans (hunting seasons, historical periods, memory) with animal and ecological timescales. The texts in Kipling’s collection ask us to move between temporal scales of magnitude that may map in one register but not in another: for example, breeding cycles that adhere to conceptions of nature but not to Anglo-Indian geopolitical timelines, or animal instincts that belong to theories of evolutionary time but challenge historical chronologies.

In The Jungle Books time is not linear or progressive. It is fragmented and multiscalar; it runs at different speeds and has its actors switch costumes mid-play. It makes us uncomfortable as readers: it undermines assertions of anthropocentrism and British dominance. It suggests that in a given ecosystem – and imperial geography – competing time spans overlap and exist in multiple tenses.

For more, see Harner, Christie. “Geopolitical Temporalities and Animal Ecologies in The Jungle Books.” Victorian Review, vol. 45 no. 1, 2019, p. 135-152. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/vcr.2019.0035.