by Elsa Richardson

Over the last decade the so-called paleo diet has garnered popularity among the health-conscious as a sure route to increased energy and weight loss. Sometimes referred to as the ‘caveman diet’, the regime assumes that modern farming practices have encouraged a way of eating that is dangerously out of step with the natural rhythms of the body. Advocates of the diet insist that instead of consuming legumes, pulses and grains -–the products of agricultural practices— we should adopt the eating habits of Palaeolithic man, who ate mostly meat, fish, nuts and vegetables. Looking back to the end of the last Ice Age for alimentary inspiration, paleo enthusiasts often call on evolutionary science to substantiate their claims, but within the field the question of what our ancestors ate and whether we should follow their example today, remains up for debate. Behavioural ecologist Marlene Zuk argues that our digestive systems have actually developed in parallel with changes to global food production and elsewhere researchers from the Evolutionary Studies Institute (ESI) at Wits University in Johannesburg have recently discovered that in parts of southern Africa starchy carbohydrates were eaten hundreds of thousands of years ago.

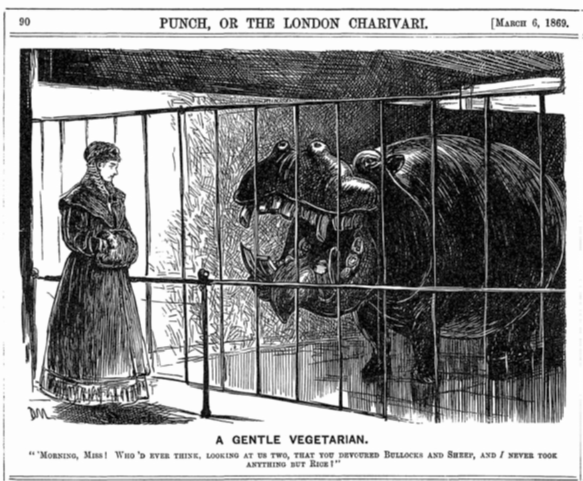

This dietary debate may seem peculiar to our wellness-obsessed age, but a similar argument was staged through the latter decades of the nineteenth century. One of the unintended consequences of the popularisation of evolutionary theory, was a growing interest –evident in not only science and medicine, but also in popular culture– with the eating habits of early humans. The subject was of particular interest to proponents of vegetarianism, who were convinced the consumption of flesh -–far from being universal and timeless— was in truth a gross distortion of man’s natural diet. Writing for the Vegetarian Messenger in 1888, George T. B. Watters cited ‘anatomical considerations’ as proof that humans are herbivorous and praised our common ancestor, the ape, for having had the good sense to stick to fruit. The consumption of animals constituted, for Watters and other evolutionarily-minded vegetarians, a betrayal of basic biology that invited illness and spread disease. Like followers of the paleo diet, nineteenth-century vegetarians saw eating out of time with the stomach as the source of many of the debilitating health problems plaguing the modern world. While today’s ‘caveman’ diet is a pretty fleshy affair, for some Victorians prehistoric man was a strict vegetarian.

To read more, see Richardson, Elsa. “Man Is Not a Meat-Eating Animal: Vegetarians and Evolution in Late-Victorian Britain.” Victorian Review, vol. 45 no. 1, 2019, p. 117-134. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/vcr.2019.0034.