by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra

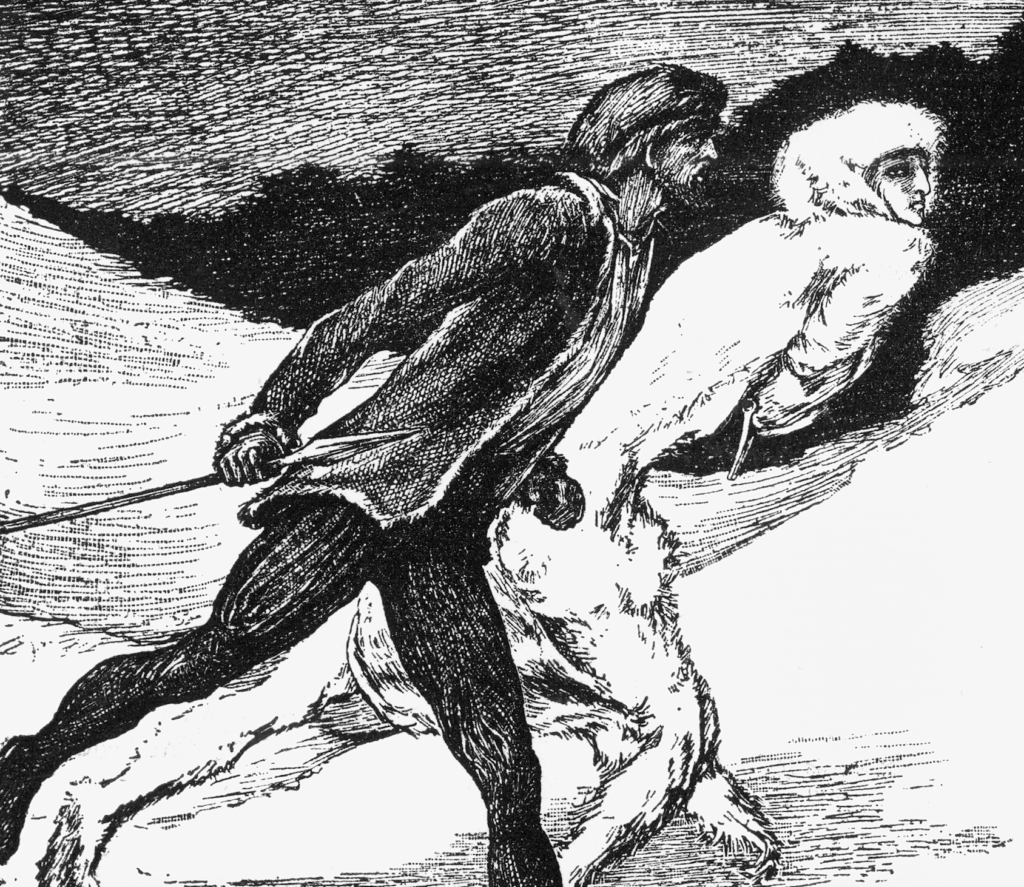

Some Victorian narratives seem to get under your skin, compelling you to read them over and over. In my experience, the ones that never let you go are by women writers who explore embodiment and transformation through the overlapping discourses of Victorian sexuality and religion. Christina Rossetti’s Goblin Market (1862) is one such text. Clemence Housman’s less well-known novella The Were-Wolf (1896) is another. I first engaged with these complex narratives as a doctoral student. Over the years I have taught both works as image/text collaborations between siblings. In each case, a brother illustrated his sister’s fantastic narrative by calling attention to the uncanny doublings at the heart of the tale. The collaborative production of The Were-Wolf was even more intense than that of Goblin Market, as Clemence Housman, an expert facsimile wood engraver, engraved her brother Laurence Housman’s pen-and-ink designs for the book edition of her gothic story (fig. 1). Recently, I co-edited annotated editions of these collaborative works for COVE Electronic Editions. Goblin Marketand The Were-Wolfare now widely available for classroom use in online versions supported by textual histories, contextual essays, and a wide array of visual materials. The Were-Wolf is sure to provoke multiple readings and re-readings by students and teachers alike.

Like all editions, my electronic re-mediation of Housman’s The Were-Wolf was an act of collaboration and interpretation. As a collaborator, I was participating in Clemence Housman’s own career-long doubling back on her gothic narrative to shape it in various forms. What did the story come to mean to her over 40 years of retelling it? And why was she compelled to do so?

In returning to The Were-Wolf after twenty-five years in the profession, what strikes me most is the urgent way in which transformation emerges in the overlapping narratives of conversion and change evoked by its religious and pagan discourses. The trope of transformation, moreover, is crucial not only to the story itself, but also to the various technologies of representation through which Housman communicated it to specific audiences in different times, places, and media. First, as an oral tale for female artisans—fellow students in her wood-engraving class in South Lambeth in 1884. Next, as the Christmas number for Atalanta (1890), a magazine for progressive girls and women, with illustrations by Everard Hopkins. Then as an illustrated gift book designed by Laurence Housman, with six laboriously carved full-page wood engravings by Clemence herself, for the lovers of beautiful things who bought John Lane’s list of belles lettres at The Bodley Head (1896). Finally, for the post-war period of mass media, a script for a silent film (1924). Throughout these transmedia changes, the constancy of the title, The Were-Wolf, calls attention to the ongoing embodied experience of transition, of always-becoming, of multiple, hybrid identity. In seeking transformation, The Were-Wolf queries transgression, asking to be read, not from constructed cultural binaries—male/female, animal/human, pagan/Christian, normative/Other— but from the fluidity of trans theory. Having no authentic body, how can the werewolf transgress?

To read more, see Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, “Clemence Housman’s The Were-Wolf: Querying Transgression, Seeking Trans/formation.” Victorian Review, vol. 44, no. 1, pp. 51-64.

To read the COVE edition of Clemence Housman’s The Were-Wolf, go to https://editions.covecollective.org/edition/were-wolf