by Scott C. Thompson

What are we to make of George Eliot’s last published work Impressions of Theophrastus Such (1879)? It’s not a novel, and it’s not narrated in the third person, two mainstays of Eliot’s literary aesthetic. Instead, it’s a series of character sketches written from the perspective of a middle-aged bachelor named Theophrastus. My article “Subjective Realism and Diligent Imagination: G. H. Lewes’s Theory of Psychology and George Eliot’s Impressions of Theophrastus Such” attempts to make sense of Eliot’s highly experimental final publication by first demonstrating its intimate connection to George Henry Lewes’s psychological theory as conceived of in his Problems of Life and Mind (1874-79) and then by positioning it within Eliot’s career-spanning realist project.

This piece began as a conference paper for S. Pearl Brilmyer’s “George Eliot and the Science of Description” class at the University of Pennsylvania. We read the second series of Lewes’s Problems, The Physical Basis of Mind, alongside Impressions. Both Problems and Impressions were written simultaneously, and Eliot helped edit, arrange, and publish the final series of Problems after Lewes’s death. Reading both texts together, I quickly realized that Impressions engages much more of Lewes’s work than just his theories on the materiality of the brain: it models Lewes’s entire psychological methodology. Problems is Lewes’s attempt to construct a method for psychological investigation that accounts objectively for subjective experience through what he calls “speculative knowledge.” Impressions fictionalizes this psychological method, and makes a case for “diligent imagination”—that is, imagination extrapolated from experience—as a means of transcending the limits of human subjectivity by extending speculative knowledge to the relationship between self and other.

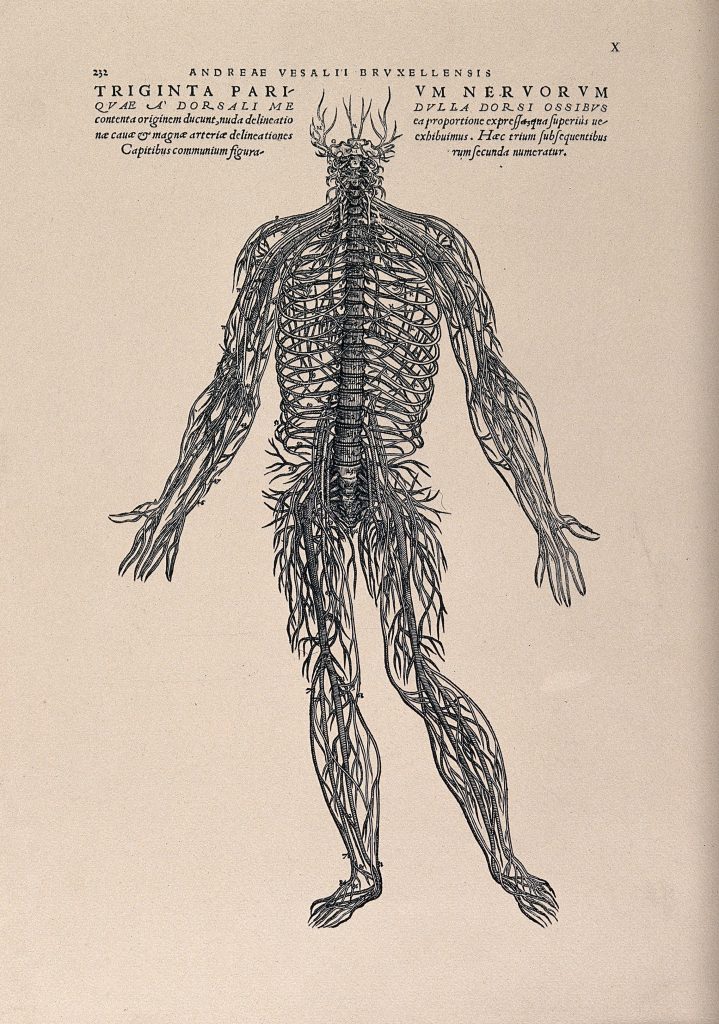

An arrangement of the spinal nerves. Photolithograph, 1940, after a woodcut, 1543. Credit: Wellcome Collection. CC BY https://wellcomecollection.org/works/bq2g5msr

So what are we to make of Impressions? It’s an exploration of Lewes’s psychological method and its limitations. It’s a meditation on the problem of other people. And it’s an argument for imagination’s crucial role in connecting people to the world and to each other.

To read more, see Scott C. Thompson, “Subjective Realism and Diligent Imagination: G.H. Lewes’s Theory of Psychology and George Eliot’s Impressions of Theophrastus Such.” Victorian Review, vol. 44 no. 2, 2018, p. 197-214. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/vcr.2019.0016.