by Amy Woodson-Boulton

During the period of the New Imperialism, c. 1870-1930, animals intruded upon the society and culture of European empires and particularly the British empire in new ways. Animals came to play a prominent role in art, literature, and ideas, but they were also physically present, and shaped discussions about class, justice, economics, imperialism, religion, and anthropology. The animals of indigenous societies from Oceania and Australia to British Columbia to Africa to India helped shape anthropologists’ ideas about those societies and cultures. That cattle, sheep, and pigs thrived across the British and Irish countryside became a question of land reform and in debates over how to feed an expanding population; that they successfully adapted to new habitats from the Americas to Australia and New Zealand furthered colonialization. The animals of Africa became a justification for British presence there, whether to save, feed, or study the indigenous people, or to study and protect the animals themselves. Beautiful, dangerous, sympathetic, delicious, promising increased health, facilitating or threatening the expansion of “civilization,” marking off “wild” territories and people, decorating hats and baronial halls, animals were omnipresent, and their presence affected relations with humans and among humans.

In particular, the question of eating and killing became a point of debate and an important point through which imperialists marked the divide between “primitive” and “civilized.” Anthropologists heatedly debated the meaning of eating and worshiping totemic animals among the hunter-gatherer peoples in the Americas, Oceania, and Africa then under (or coming under) European control, understanding these peoples (or at least their cultures) as mostly doomed to extinction, and in terms of set stages of social evolution. But even in seemingly unrelated cultural arenas, such as in the vegetarian movement or among big-game hunters, we see people applying similar logics about animals, identification, and consumption. Anthropologists, vegetarians, and hunters debated and defined “civilized” and “primitive” relationships with animals around questions of ingestion, relation, and prohibitions around what constituted allowable “meat” and what was prohibited (or sacramental) “flesh.”

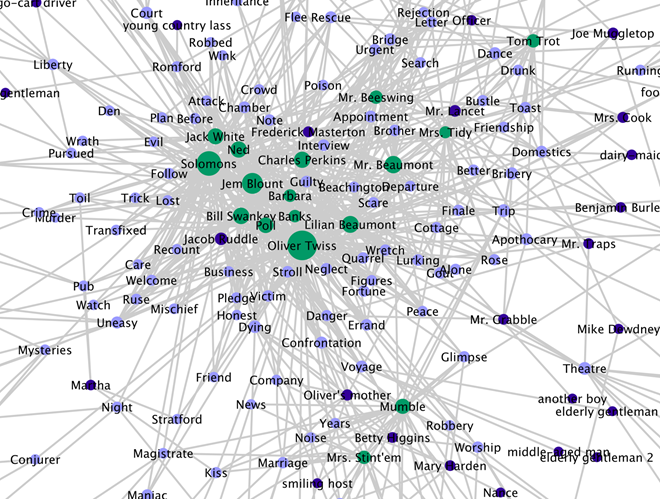

The idea that animals are “good to think [with]” has become a truism in Animal Studies; scholars on both sides of the animal-agency divide, or debating various questions of social and cultural construction, have often used this declaration by Claude Lévi-Strauss as a foil for their own theories or arguments. But few in Animal Studies have considered the original context of that statement: Lévi-Strauss’ deconstruction and rethinking of the Victorian theory of totemism. This article considers how that theory was part of not only changing ideas about animals and human-animal relations at the height of British imperialism, but how those ideas were in fact responses to this growing presence of animals and animal products through imperial trade systems. In the shadow of Darwinian natural selection and new theories that connected animals to humans in radical ways, and surrounded by and dependent on animals and animal products, the late Victorians were constantly pushing animals and the “primitive” away even as they tried to understand all of history and biology on the spectrum of evolution. Animals were crucial to their own societies and systems of thought; they were both “good to eat” and “good to think,” and not just for “primitive” societies.

To read more, see Woodson-Boulton, Amy. “Totems, Cannibals, and Other Blood Relations: Animals and the Rise of Social Evolutionary Theory.” Victorian Review, vol. 46 no. 2, 2020, p. 211-233. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/vcr.2020.0020.