by Denae Dyck

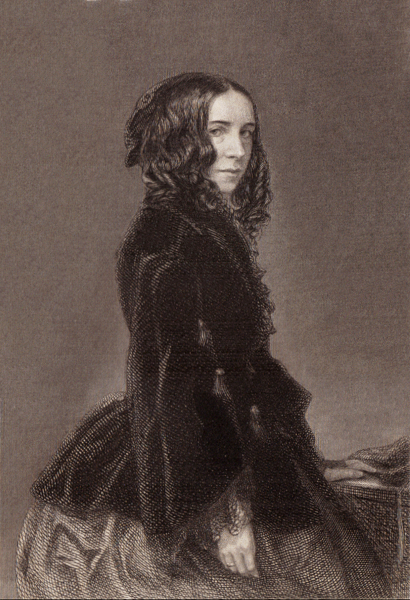

Today, many people remember Elizabeth Barrett Browning (hereafter, EBB) primarily for her collection Sonnets from the Portuguese (1850). But in addition to this romantic sequence composed for Robert Browning, EBB wrote a wide variety of poems that responded to a range of social, religious, and political issues. Perhaps the most controversial of her politically engaged compositions is “A Curse for a Nation.”

This lyric poem begins with a prologue in which the speaker recounts a dream vision about an encounter with an angel who summons her to write a curse pronounced against an offending (and unnamed) nation. The speaker initially protests, but she concedes after the angel challenges her understanding of what it means to curse. She then issues the curse as a powerful combination of warning and promise—a moral awakening that implicates the speaker and ultimately reaches toward readers as well. What is most striking to me about this poem’s religious and political rhetoric is its adaptation of the prophetic voice. Rather than rebuke a single “chosen people,” the poem uses the framework of prophecy to advance a pluralistic understanding of social justice, one that redefines conventional ideas about both cursing and nationhood.

The poem’s international scope is immediately apparent in its publication history, but I suggest that this work of redefinition invites close attention to its linguistic and structural patterns. “A Curse for a Nation” first appeared in the 1856 issue of the Boston abolitionist The Liberty Bell, a context that made the poem’s anti-slavery message apparent: the nation in question is clearly the United States of America. However, a few years later, EBB republished this poem in Poems before Congress (London: Chapman and Hall, 1860), a volume that focused on the struggle for Italian unification and independence known as the Risorgimento (Italian for “resurgence” or “rebirth”). In this context, many of EBB’s initial British reviewers interpreted the poem as a malediction against England for its failure to aid the Italian cause. EBB protested that this reading was a misinterpretation, yet “A Curse for a Nation” aligns in notable ways with the cosmopolitanism advanced elsewhere in Poems before Congress by this expatriate poetess, who lived primarily in Florence from 1847 until her death in 1861.

As signalled by the two indefinite articles in the poem’s title, “A Curse for a Nation” is ambiguous—but productively so. Through the conversation that unfolds between the angel and the speaker, the poem progressively redefines what a curse is, how it is delivered, and who may utter it. Like many other nineteenth-century writers, such as Thomas Carlyle and Matthew Arnold, EBB uses prophetic discourse for the purpose of social critique. Even so, EBB is unlike many of her contemporaries because she portrays this divine revelation not as a static denunciation but as a transformative dialogue. Whereas Carlyle takes up the prophetic voice to call attention to “the condition of England” question in Past and Present (1843), EBB addresses what might be better termed “the condition of humanity” as she calls her readers to take up their ethical obligations to a worldwide community. The poem’s performative language compels us to wrestle with challenging issues of identity, authority, and citizenship.

To read more, see Denae Dyck, “From Denunciation to Dialogue: Redefining Prophetic Authority in Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s ‘A Curse for a Nation.’” Victorian Review vol. 46 no. 1 (Spring 2020), pp. 67-82.