by Anna A. Berman

Think of a nineteenth-century English novel that features a significant sister-sister or sister-brother pair. Easy, right? Now think of an English novel about two brothers.

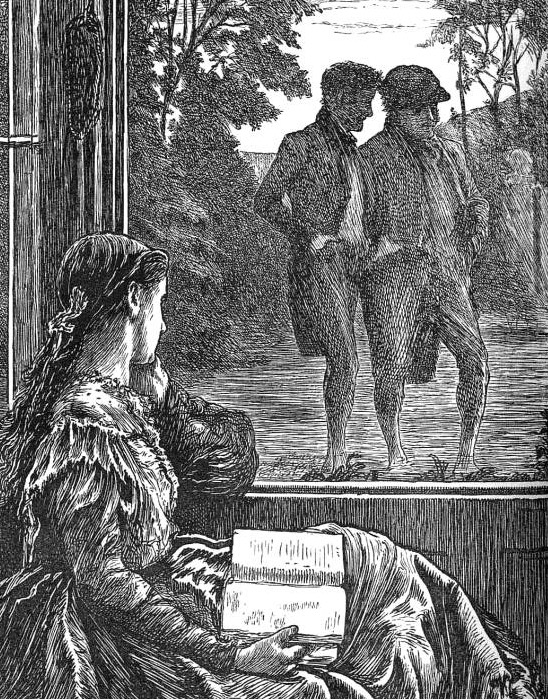

As someone who began by studying Russian literature—which is full of brothers—it came as a shock to me when I realized that there are virtually no canonical English novels that focus on a brother-brother pair. Given the Victorians’ reverence for the sibling bond, why is strange omission? And why do the rare novels about brothers almost always have the same plot: two brothers—the “most faithful of friends”—fall in love with the same woman? (think of George Eliot’s Adam Bede, Wilkie Collins’ Poor Miss Finch, or Mary Elizabeth Braddon’s Like and Unlike)

Comparing the English with the Russian tradition gave me my first clue to the answer. One of the primary differences between the two nations—as far as brothers are concerned—is that the English honored primogeniture, while the Russians split their estates amongst all their children. This has major implications for the types of plots authors in each nation could create. Courtship is central to English family novels, and with wealth as a requirement for single men in want of wives, only one brother had a desirable place in the English marriage plot.

This fact goes far in explaining the standard English brother-plot of romantic rivalry. Having a single beloved for the brothers helps maintain the linearity of the family and plot. While the Russians thought of family as a conglomeration of kin in the present and wrote “loose and baggy monster” plots that sprawl in all directions, the English focused on the family’s progression through time; wealth and title were to be kept together and passed on to a single heir who would continue the family line.

Brothers offer a challenge to this focused structure, but that challenge can be mitigated if only one marries and produces heirs. In the English novel, the brother who loses the romantic competition is removed from the family’s linear progression to restore harmony at the novel’s close. Most often he dies, or else he is turned into a “sister” who remains unwed and cares for his brother’s children (e.g. Seth Bede or John Martindale in Charlotte Yonge’s Heartsease or Brother’s Wife).

The two-brother-one-lover triangle also suggests mimetic desire at work. When—in novel after novel—brothers who describe their relationship as “something more than affection” and consider the other to be “an angel” fall in love with the same woman, it opens room for speculation that such romantic triangulation might be a strategy for displacing an illicit form of desire onto a “safe” object. The brothers’ romantic rivalries could be seen as a way of neutralizing an initial threat of incestuous, homosexual desire entering the family by replacing it with the more openly addressable threat of jealousy and hatred, which could then, in turn, be resolved. In essence, this resolution is the primary plot for English brothers.

The role of brothers is but one example of what looking comparatively at the Russian and English family novel can reveal. Such an approach forces us to rethink existing theories of the novel that assume a conservative function for the family, driven by the genealogical imperative and linear descent, and offers a new understanding of how family structure shapes plot in the nineteenth-century novel.

To read more, see Anna A. Berman, “The Problem with Brothers in the Nineteenth-Century English Novel.” Victorian Review, vol. 46 no. 1, 2020, p. 49-66. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/vcr.2020.0008.