by Hosanna Krienke

The year 2020 has repeatedly witnessed male world leaders struggle to appear virile and masculine in the midst of physical illness and recovery. Britain’s Boris Johnson, Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro, and of course the United States’s Donald Trump have all fallen ill with the coronavirus, a development that appeared to necessitate a shoring-up of their hyper-masculine political personas. In April, Boris Johnson’s aides insisted that the hospitalized prime minister was “still in charge of the government” even on the very day he was moved into intensive care. In July, Bolsonaro also contracted the “little flu” he previously dismissed, though he went on to tout his own recovery as a sign of his athleticism. Most recently, the White House counteracted the apparently unmanly optics of Trump’s hospitalization by releasing photos of him signing paperwork within the hospital, images that circulated on Twitter with the tag #TrumpStrong.

In each case, our cultural expectations surrounding a man’s experience of illness have played out predictably. Men perform their masculine resilience by refusing to give up work even as they fall ill; then, when no longer able to work, they redirect this strength to the Herculean task of achieving a speedy recovery. In a recent piece for The Atlantic, science journalist Ed Yong analyzed how the omnipresent metaphor of “strength” in the Trump recovery narrative is an inappropriate image for physiological illness, and particularly the biology of the immune system. Yet as I watch this narrative play out again and again within the news cycles of 2020, what I am struck by is the utter lack of alternative metaphors or values for the process of physical recovery, particularly for men. Though the work of Susan Sontag as taught us the dangers of using terms like “battle,” “fight,” and “strength” when it comes to physical disease, the question remains: if we abstain from these metaphors, what other language do we even have?

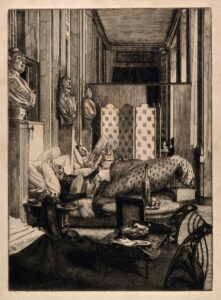

My essay in this edition of Victorian Review actually uncovers an alternative, forgotten history of men’s recuperation or (as it was more commonly termed) convalescence. Far from a battle or fight, convalescence in the nineteenth century represented a welcome relief from the stresses and demands of modern life. Many Victorian male writers—including W.E. Henley, George Whyte-Melville, and Wilkie Collins—even described their convalescence a beneficial reprieve from the taxing demands of masculinity itself, particularly the norms of overwork. These writers unabashedly reveled in the leisure of convalescence: the medical directive, as so many put it, “to do nothing.” In fact, this luxurious respite prompted an ethical awakening for some authors. Wilkie Collins, in particular, described how convalescence made him recognize the unsustainable work pressures—not of his own gender and class—but of the maids-of-all-work who provided his care. Using this context, I discover how Collins’s The Moonstone refashions novel-reading itself as a kind of ethical, restful convalescence: a necessary and illuminating respite from one’s average routines and social roles.

Such imagery of leisurely, pleasurable, and unexpectedly ethical ideals of prolonged physical recovery may seem utterly unfamiliar today. Yet we are seeing more evidence every day of our desperate need for new—or perhaps very old—narratives structures to describe the opportunities and responsibilities of bodily recuperation.

To read more, see Hosanna Krienke, “”The Wholesome Application” of Novels: Gender and Rehabilitative Reading in The Moonstone.” Victorian Review, vol. 46 no. 1, 2020, p. 83-99. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/vcr.2020.0016.