by Lisa Hager

As someone who is both a Victorian studies academic and a partner to a trans masculine person, I see my recent article on “A Case for a Trans Studies Turn in Victorian Studies,” as in many ways, a love letter to both the academic and trans communities that occupy such important places in my life. It began with a seemingly simple question that Joseph Bristow asked me many years ago as I was telling him what I was currently working on: “Where is the trans studies work in all of this?” In the moment, I brushed aside the question, telling him that my current Victorian studies work didn’t intersect with trans-focused activism and communities of my personal life. Fortunately, like many important questions, the question wouldn’t go away, and I kept hearing it in my head as I continued to work on other projects.

As I went about the usual business of my academic life—attending conferences, writing articles, teaching classes—I couldn’t help but notice how Victorian studies as a discipline had yet to deeply engage with the core trans studies idea that assigned-at-birth-gender does not equal a person’s (or a character’s!) gender. In short, Victorian studies had yet to fully grapple with the existence of transgender people in our time and throughout history since gender itself has existed.

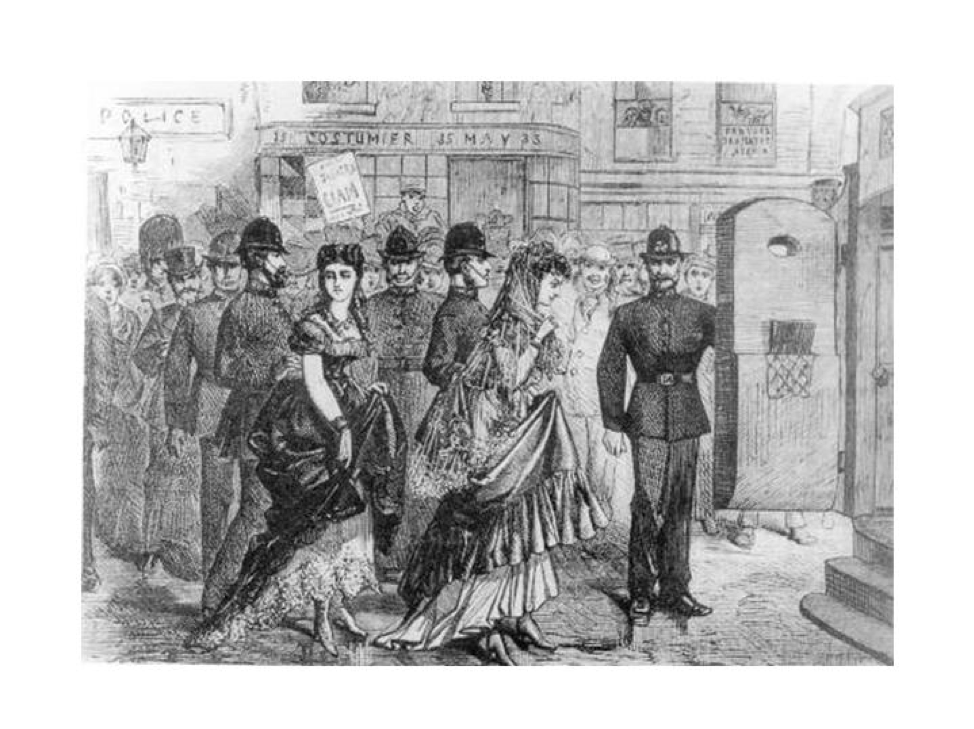

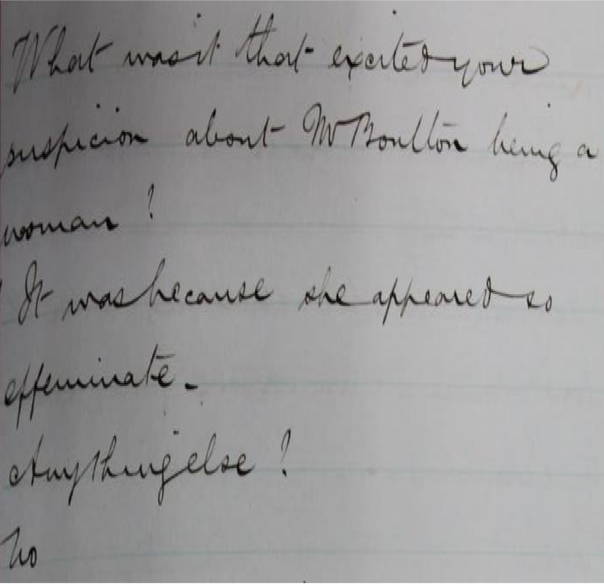

In particular, this absence of a trans-inclusive conception of gender was made especially clear to me when I came across scholarly discussions of nineteenth-century “female husbands” that assumed without question that such people were women who masqueraded as men in order to marry other women. Instead, as my article argues at length, we must parse out relationship between the gender identities and sexualities of these people to better understand the highly mediated narratives about them. In doing so, the persistence with which the men whom the periodical press termed “female husbands” (usually after the so-called “discovery” of their designated at birth gender) insisted on and fought for their gender identities as men, even the absence of a partner, calls on present-day academics to honor their identities as men and to situate them within transgender literary history. Moreover, this approach enables us to see how the commonalities and connections between the narratives created around such men not only shape modern-day discourses around trans identities but also our understanding of gender itself.

To read more see Lisa Hager, “A Case for a Trans Studies Turn in Victorian Studies: “Female Husbands” of the Nineteenth Century,” Victorian Review, vol 44, no 1, pp. 37-54.