By Anika Zuhlke

In 1878, the Liverpool Mercury published a piece titled “Our Mysterious Goldfish.” In it, the writer, W.F.P., relates that they purchased three small goldfish for their outdoor pond. The fish were left outside during a series of frosts, and one perished. They were then transferred to an indoor globe, but the smallest, named Tiny, soon evinced signs of illness as well and was dutifully placed in a separate bowl in a warm corner of the kitchen. Tiny revived—only to leap into the coal box overnight, where he was found seemingly dead the next morning. Hours later, however, W.F.P. was astonished to find that Tiny was in fact alive, “battered and begrimed, like a prizefighter and coalheaver rolled into one.” “Surprised and incredulous” by this “marvellous return from death to life,” W.F.P. begs to submit Tiny’s case to a naturalist, asking how a “poor little goldfish in delicate health” could not only survive a tumble into the “unnatural” space of the coal scuttle, but “conduct and disport itself as if nothing unusual had happened” once returned to its bowl. “As for myself,” W.F.P. concludes, “I candidly confess I am growing afraid of Tiny … he is proving himself too much for us. Unless he amends and learns to live quietly and respectably, we shall be compelled to pack him off to the Brighton or some other aquarium.” W.F.P. no longer seems to know precisely what a goldfish is, or where it belongs. They survive “unnatural” spaces and, by extension, their nature is called into question; they are a case for the naturalist.

The Liverpool’s article was just one of many curious anecdotes about goldfish to surface in the periodical press in the UK and US from the 1870s to the 1910s. Newspapers reported instances of goldfish surviving leaps from their bowls, playing pranks on other species, and outliving their owners. Indeed, from the relatively tame assertions that goldfish never slept, that they could predict storms, or that they could be trained, to the more bizarre claims that they did not need to be fed, would not displace water, or could survive being frozen solid, periodicals conferred upon the goldfish a surprising range of abilities and hidden talents—some of which seemingly bent the laws of nature.

This flood of attention was in part triggered by a shift in how the goldfish was perceived. Earlier, during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, goldfish were typically represented as timeless products of the “Orient,” emblematic of beauty, wealth and tradition. Common goldfish “are shaped pretty much like the Carp,” one eighteenth-century naturalist explained, and so their exoticism was tempered by a sense of familiarity (Edwards 209).

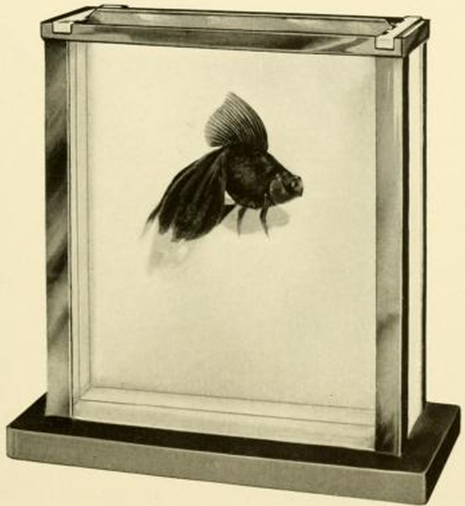

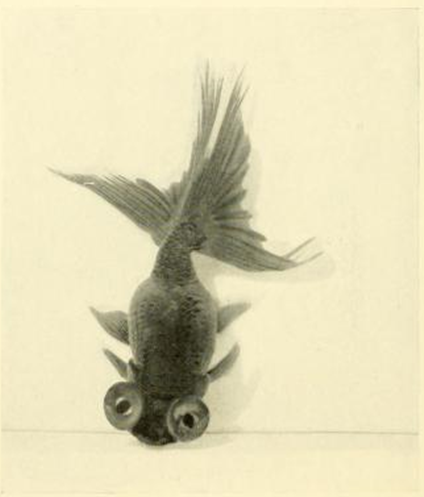

By the 1870s and 1880s, however, the Victorians had been introduced to fancy goldfish breeds newly imported from the East. In comparison to common goldfish, which vary in colour and fin shape, and might have one or two tails, the morphological variability of fancy goldfish would have been astonishing: not only do many have globular bodies, and fins and tails that vary considerably in shape, size, and number, but several breeds boast distinctive structural traits such as protruding head growths or bulging “telescope” eyes.

While many commentators admired these new varieties for their beauty, others worried that they were unnatural aberrations, problematizing the “freaks and unusual developments” (“About Goldfish”), “bizarre forms,” and “hideously” and “enormously exaggerated” fins and eyes propagated by (foreign) breeders (“Keeping Gold Fish”). Human interference in the species’ development prompted consternation as reports circulated of egg-shaking, fin-shearing, and bizarre rearing conditions, and Darwin himself had difficulty distinguishing between the goldfish’s “variations” and “monstrosities” (296-97). No longer simply the pretty and placid parlour ornament of the preceding century, the figure of the goldfish had become more complex, caught somewhere between nature and artifice, tradition and change, familiarity and “other,” and containment and transgression.

My article, “Frames of Glass: Goldfish and Gender in Paint, Performance, and Print, 1870-1914,” takes up this stream of discourse where it intersects with late-century gender debates. Drawing upon examples from fine art, novels, popular journalism, travel writing, and theatre, I examine how goldfish were used to grapple with shifting patterns of femininity at a time when the Woman Question was inflected by biologically deterministic arguments about women’s “natural” societal roles. By drawing (or disrupting) analogies between women and goldfish, artists and writers explored questions about the nature of women, the extent to which the natural order was being eroded or endorsed by change, and the possibility that women would increasingly compete with men. By analysing this hitherto unexamined alternative to the “bird in the cage,” my study of the goldfish and its bowl provides insight into how the Victorians’ confrontations with other species encouraged them to look more critically at themselves.

Works Cited

“About Goldfish.” Hampshire/Portsmouth Telegraph, 24 July 1897.

Darwin, Charles. The Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication. 1868. Cambridge UP, 2010.

Edwards, George. A Natural History of Uncommon Birds. Vol 4, London, 1751.

“Keeping Gold Fish.” Milwaukee Journal, 25 Aug. 1888.

W. P. F. “Our Mysterious Goldfish.” Liverpool Mercury, 12 Apr. 1879. British Library Newspapers.