Ge Tang, University College Dublin

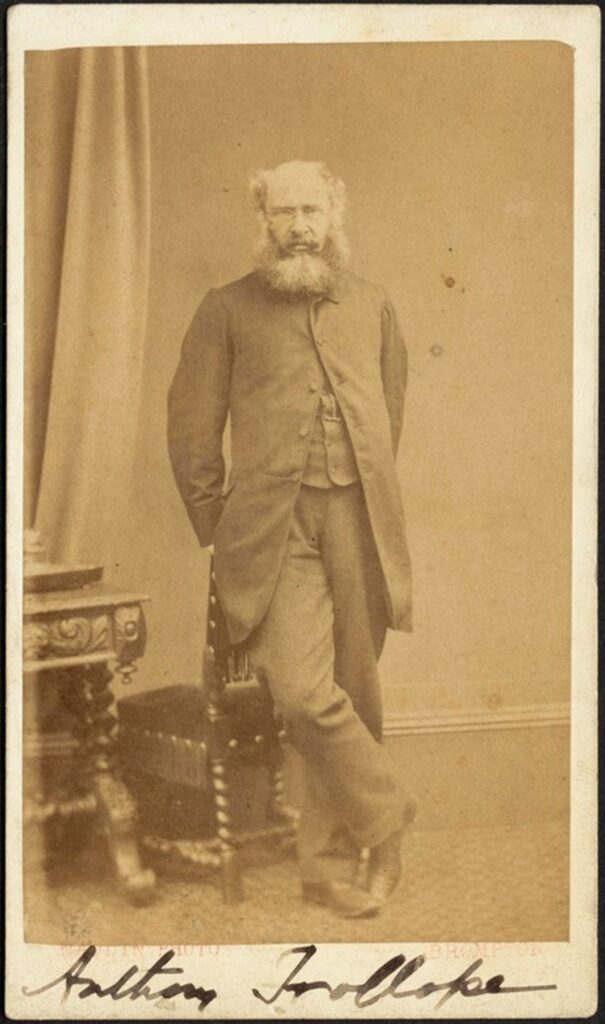

In this photograph stands Anthony Trollope fully clad in black: a black vest buttoned-up, black trousers, black shoes, and a long frock coat. The colour and tight cut of his attire reflect the prevailing men’s fashion of his era which celebrated a sense of discipline, moral integrity, and professionalism. His penetrating gaze complements the severity and solemnity of his attire. This photograph of Trollope (and, in fact, his other surviving photographs and portraits) suggests his acute awareness of this clothing culture, as well as his determined efforts to harness its symbolic power in gentle society. Yet, I cannot help but also notice the slightly strained fabric of the vest and the coat that pulls across his midsection. The close-fitting cut does not appear to suit Trollope’s stout figure, likely restricting his movement and inducing some bodily discomfort. How would his sensory experiences with attire inflect his ideas of sartorial symbolism? My Victorian Review article explores Trollope’s heightened consciousness of his clothing’s materiality in his travelogue The West Indies and the Spanish Main, born out of his Caribbean trip, highlighting the interconnected agentic forces of his clad body, his attire, and the tropical environment. I show how Trollope’s bodily feelings induced by clothing’s materiality in the tropics prompted him to rethink its cultural meanings, while it also shaped and reshaped his sartorial practices during his travels.

Trollope sailed to the Caribbean in November 1858 for a mission assigned by the British post office, which he had served for more than a decade. He was tasked to negotiate with authorities in Jamaica and British Giana for the transfer of colonial post offices to local control, while he also needed to persuade Spanish possessions in Cuba and Puerto Rico to lower the fees for forwarding mail (Super 100). Given his mission’s significance for building imperial connectivity, diplomacy in his attire was as crucial as diplomacy in his negotiations with high-standing colonial figures. In addition, to show courtesy to the British Caribbean society with whom he mingled, Trollope was expected to follow the sartorial style they had transplanted from home to retain “Englishness” in the tropics. We hear Trollope complain in the travelogue that he “must appear in black clothing, because black clothing is the thing in England” (45). Yet, neither the heat-absorbing colour of black nor the fit of his attire were appropriate for the oppressive tropical heat and humidity faced by Trollope. Driven by his bodily discomfort in unbreathable, black dress, Trollope sensibly, and emotionally, condemns this cultural transplantation: “[i]f a black coat, &c., could be laid aside anywhere as barbaric, and light loose clothing adopted, this should be done here” (45).

My article highlights that Trollope’s attire exerts an agentic force over his inappropriately clad body through clothing’s materiality, especially the colour, the fit induced, and the texture. Attire- bodily discomfort under the heat promotes him to recognize the materiality of clothing and the importance of adapting it to the environment. In Spanish Town, Jamaica, Trollope disregards the warning that “The Governor won’t see [him] in that coat,” visiting him without changing it for a socially approved one (45). He recalls with pride, “The Governor did see me” (45). His standing as a representative of the British Empire certainly enables him to bend local sartorial rules to privilege bodily comfort. Contending with heat-induced digestive discomfort and even physical breakdown, Trollope turns to alternative forms of clothing to fashion his English masculinity and to assert symbolic mastery of a foreign land already colonized by Britain. His attempt, however, as demonstrated in my article, is thwarted by tropical ecosystems that demand him to contemplate and even recognize the land’s environmental and cultural alterity.

References

- Super, Robert Henry. The Chronicler of Barsetshire: A Life of Anthony Trollope. University of Michigan Press, 1988.

- Trollope, Anthony. The West Indies and the Spanish Main. 6th ed., Chapman and Hall, 1867.