Meegan Kennedy, Florida State University

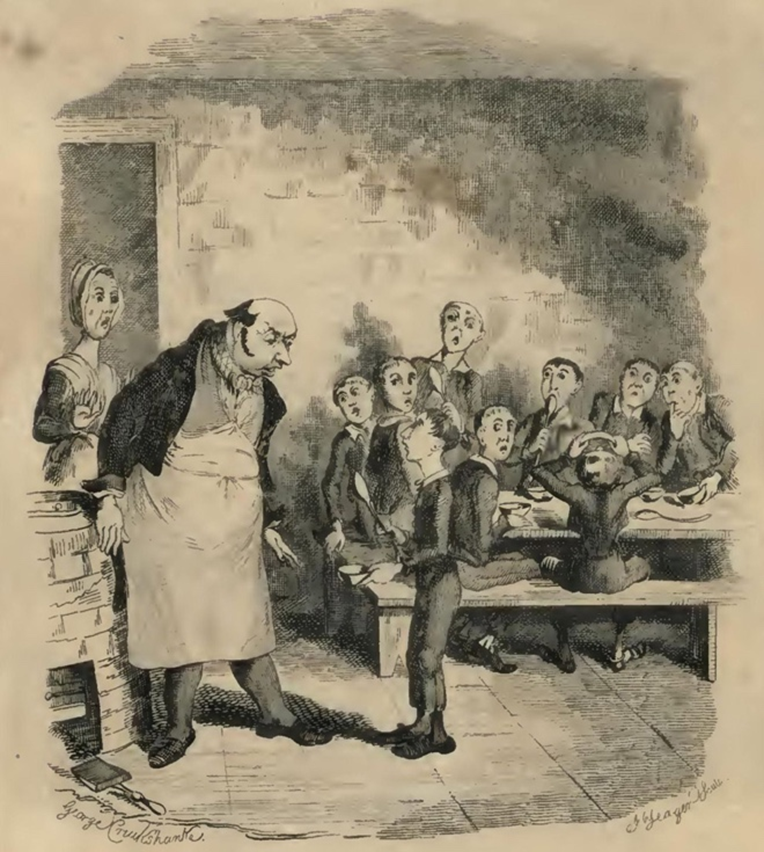

When I teach Charles Dickens’s novel Oliver Twist, I notice that students are often frustrated by Oliver’s passivity in the face of so many wrongs. Oliver moves through many different settings in the novel—baby farm, workhouse, apprenticeships with a chimney sweep, undertaker, and crime syndicate, safe havens in the city and country. But with scant exceptions, he has little control over his movements and seldom speaks; others generally move him and speak for him. Even Oliver’s famous plea for more gruel only occurs after prodding from other boys.

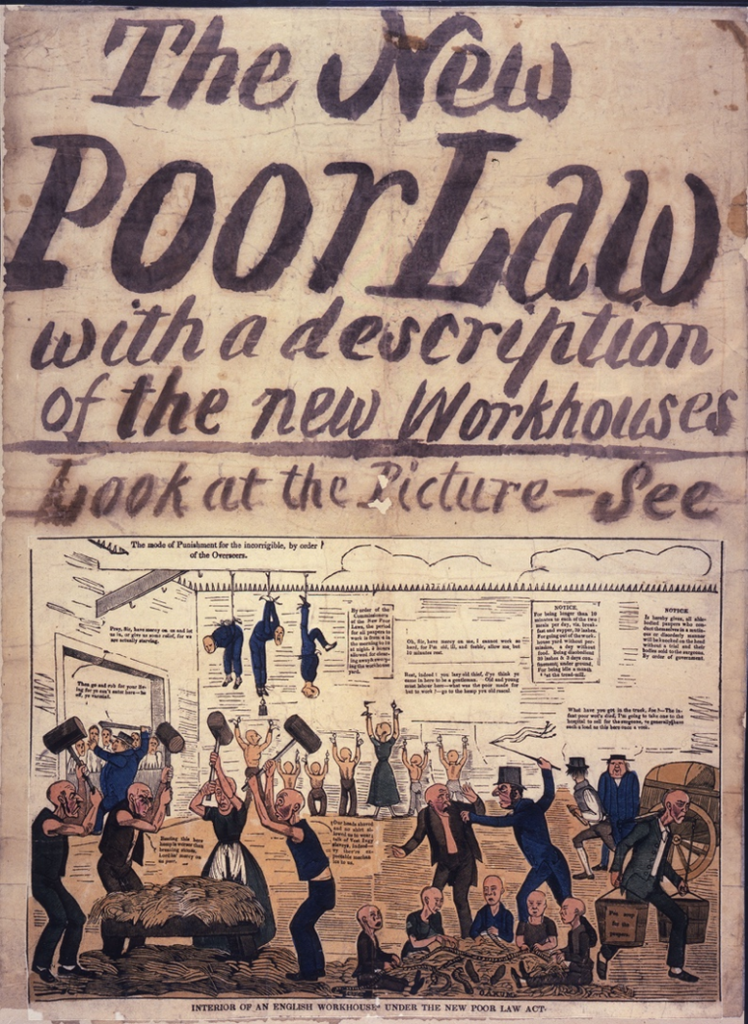

Students come to Oliver Twist conditioned by the many novels, memoirs, and films they’ve encountered that present inspiring stories about protagonists struggling and ultimately triumphing over adversity. From Maya Angelou’s I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings to Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis, from Harry Potter to Disney’s Mulan, young protagonists often challenge and inspire readers as they learn to define the self and push back against oppressive social constructs. But students are baffled by Oliver, who is anything but rebellious despite the outrageous institutional and personal abuses that children like him suffered under the 1834 New Poor Law. The law turned away from local control of public welfare, embracing instead Jeremy Bentham’s utilitarian philosophy, the new “numerical method” of statistics, and the quantification of public policy by a developing metropolitan class of administrators. It was widely decried for its harsh effects, especially on families and children. As the novel opens, Oliver is a generic “parish boy,” orphaned and indigent, without distinguishing features. Dickens shows how quickly he was “badged and ticketed” into this bureaucratic system. He becomes less than human, more an object than a person.

Some scholars have accounted for Oliver’s lack of personal growth and action by arguing that Dickens was, in 1837, still learning as a novelist. They find psychological complexity and development more often in his later novels, which more clearly fulfill the genre of the Bildungsroman.

But Dickens was playing with quite different genres for Oliver Twist. The novel weaves together elements of allegory, parody, statistical report, it-narrative, captivity narrative, Newgate novel, and finally romance. Many of these genres not only accommodate but demand a certain flatness of character. The genres Dickens explores in Oliver Twist support his argument that the New Poor Law treats thinking, feeling individual people as units exchangeable at will. The flatness of Oliver’s character dramatizes this critique. Where a novel of development would emphasize individual struggle, Oliver Twist instead turns its focus on systemic oppression.

Dickens especially uses the statistical report and it-narrative to demonstrate the human cost of the New Poor Law, and to show how utilitarianism and the new law constrain the richness of human experience. Dickens’s serialization of Oliver Twist was interrupted by the parodic statistical reports he published from “the Mudfog Association for the Advancement of Everything,” which mock the inadequacy of statistical thinking.[i] Even more intriguing, Dickens draws upon it-narrative (also known as object-narrative or novel of circulation) as another model for Oliver Twist. It-narratives are one of many older forms that Dickens repurposed in crafting his novels. These picaresque tales are told from the perspective of an object—a guinea, a pincushion, a shoe, or other non-human object, or an animal or other living creature—that is circulated throughout diverse social settings, from owner to owner, in adventures that depict the object’s inability to direct its destiny as it rotates through a wide range of various roles and contexts.

[i] Charles Dickens, “Full Report of the First Meeting of the Mudfog Association for the Advancement of Everything.” Bentley’s Miscellany, vol. 2, October 1837, pp. 397-413.

The typical it-narrative exposes the affective damages of circulating so briskly and powerlessly through a capitalistic, bureaucratic society. In Oliver Twist, the it-narrative and its object-protagonist apply moral pressure to the category of the statistical unit. Using this frame, Dickens can expose, dramatize, and condemn the utilitarian system that dissolves human identities and connections, and solidifies financial ones—for the role of an it-narrative is to show how the protagonist is not just an unthinking object. Indeed, Oliver eventually comes into focus as what Bill Brown calls a thing—an object that shows up the systems within which we act, by resisting our unthinking use.[i] Oliver’s very inertness allows him to resist those who seek to control or use him. He’s frustratingly inept, with a lot of crying and fainting, and his frail body keeps failing when faced with the rigors of chimney sweeping or crime.

Over time, Oliver becomes, in John Plotz’s terms, a “sentimental object”: he personifies a modern tension between what is on the one hand, common, commodified, indistinguishable, and exchangeable (like a guinea or lump of coal) and on the other hand, distinctive and sentimentalized.[ii] Because Oliver doesn’t quite function within a utilitarian narrative, his friends manage to pull him into a new narrative life where he becomes a proper subject and a protagonist. He finally achieves recognition as a particular young gentleman at the end of the novel—although even then he enters into this romantic role largely due to his inherited identity and the efforts of his friends Nancy, Rose, and Mr. Brownlow.

Overall, Dickens’s experiments with genre in Oliver Twist enable the work of the novel: to dramatize systemic oppression and to lift Oliver out of the brutal jurisdiction of the New Poor Law and propel him instead toward a more humane (though unlikely) horizon. When students learn about how genre relates to character and plot in Oliver Twist, they can more clearly see not just the novel’s social critique but also, more generally, how the stories we tell shape our work in the world.

[i] Bill Brown, “Thing Theory,” Critical Inquiry, vol. 28, no. 1, 2001, pp. 1-22.

[ii] John Plotz, Portable Property (Princeton: Princeton UP, 2008), p. 28.