By Dr. Emma Ferry

Barely suppressing squeaks of excitement in the hushed atmosphere of the Manuscripts Reading Room in the British Library, I squinted my way through Margaret Oliphant’s letters to and from her editors at Macmillan about her book on dress. This was my fifth foray into the Macmillan Letterbooks to investigate the ‘Art at Home Series’, but easily the most entertaining.

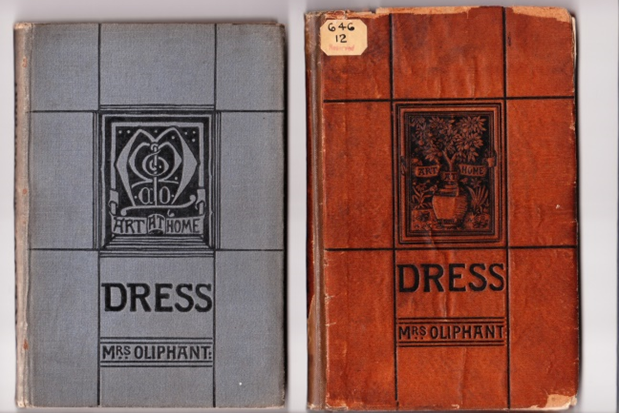

Here, among these huge volumes of correspondence were the details of Oliphant’s initial commission; non-committal discussions about the book’s subject; gentle reminders about intended deadlines and abject apologies about inevitable delays; worries about its illustrations; plaintive enquiries about the author’s fees; and, finally, the receipts for both manuscript and payment. Risking my eyesight, I painstakingly transcribed Oliphant’s appalling handwriting to piece together the story of the book’s publication, which appeared as part of Art at Home Series in both the UK and USA in 1878.

Published in London by Macmillan & Co., and in Philadelphia by Porter & Coates

Chalk sketch by Frederick Augustus Sandys (1881)

NPG 5391 © National Portrait Gallery, London

While this aspect of the book’s production was there to find among the carefully catalogued letters, tracking down the content, both textual and visual, was even more enjoyable. It became a delightful game to identify the ‘materials’ from which her Dress was made. Ranging from Chaucer to Carlyle and from Pope to Punch, Oliphant’s book was as much a journey into English fiction as it was into English fashion. Addison’s articles from The Spectator were patchworked with Spenser’s Faerie Queene while Herrick’s sensuous poems were woven together with Ruskin’s prurient advice to young women. Her own writings, carefully unpicked from novels, reviews and opinion pieces, were also re-fashioned, padded out with the antiquarian costume books of Planché and Fairholt through which she rummaged to find suitable examples of dress from the past. Resulting in less than helpful suggestions for those anxious to know what to wear, Dress is peopled with fictional and factual characters notable for their sartorial sensibilities or silliness: the Wife of Bath and Captain Bobadil are paraded alongside Sir Walter Raleigh and Oliver Goldsmith. All in all, this was a delightful dip into the button-box and ragbag of Oliphant’s literary and historical interests, with the poems and plays quoted from at length quickly identified using simple online searches: thank you Google!

Similarly, the illustrations, provided by Richard Holmes, Queen Victoria’s Librarian, were also copied from original images with varying degrees of success. Ranging from miniatures and portraits in the Royal Collection to contemporary fashion plates published in Harper’s Bazaar, these provided even less useful advice for the intended reader. However, tracking them down was a real pleasure. Hours spent searching through the online image collections of the Royal Collection Trust, the British Library and the National Portrait Gallery is never time wasted. Imagine the satisfaction of discovering the originals, still recognizable even allowing for Holmes’ lack of skill with his pen.

Having unpicked Oliphant’s Dress in my article, I have aimed not to ‘depreciate’ the author by showing where she found her ‘finest lines and most powerful effects’, but to explain how the book was made. If Mrs Oliphant were one of my students, we probably would be discussing academic misconduct and at least more effective use of careful referencing! Combining correspondence with a close reading of Oliphant’s text, my analysis challenges the prevailing view among dress historians that Oliphant was an ardent dress reformer and reveals her skills at writing with scissors.