by Sean Mier

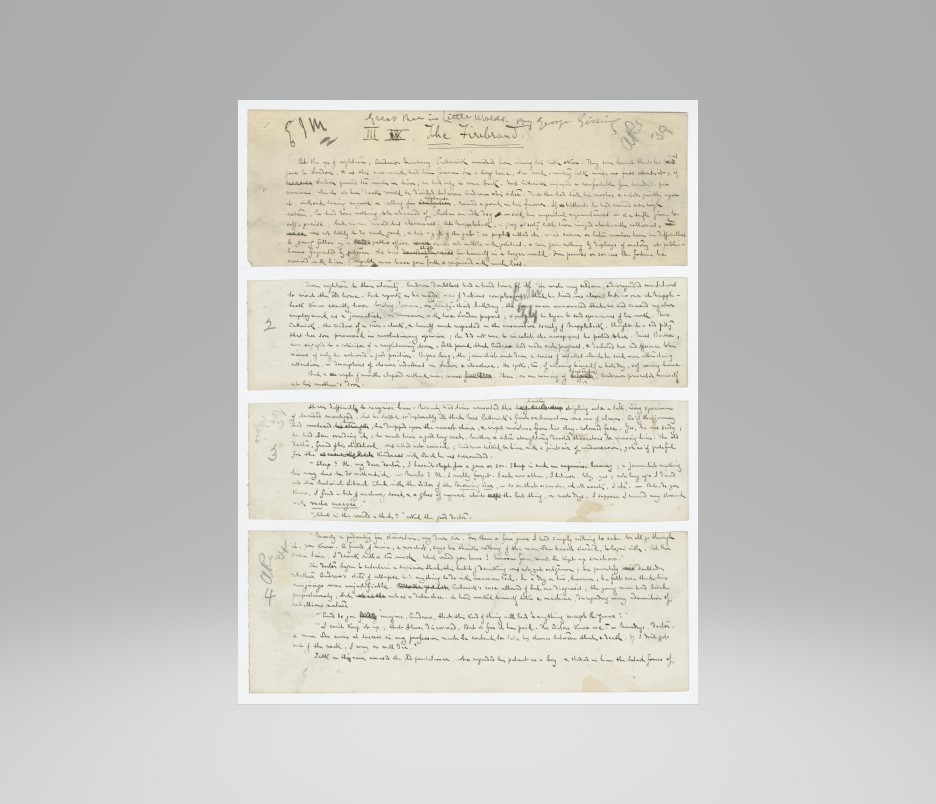

Compared to the shapely legibility of George Gissing’s earlier writings, the drafts of New Grub Street (1891), notably, and all his manuscripts that would follow instead showcase a uniquely miniaturized hand, nearly illegible to the naked eye, each page crammed with tiny words. While I was exploring the historical archives in the Lilly Library at Indiana University, Bloomington for the first time, Gissing’s microscopic holographs provoked in me a new mode of inquiry, akin yet distinct from hermeneutical approaches and even from analyses of textual revision and variation over time. Instead, the archive revealed a compositional landscape in which the materiality of Gissing’s handwriting seemed to contribute to textual meaning just as much as linguistic, narrative, and/or generic considerations might have allowed. Why would an already published author like George Gissing abruptly change his handwritten style in such a dramatic way years into his professional career? Was his adoption of a miniscule handwriting an individual quirk or rather a response to an external demand from the literary marketplace?

In the essay, I argue that Gissing’s compositional idiosyncrasy fittingly concretizes many of the same anxieties expressed in his contemporaneous, self-conscious three-volume novel about the state of professional authorship near century’s end. Specifically, H.G. Wells claimed that Gissing’s adoption of a microscopic hand allowed him to visually conceptualize and measure the length of a manuscript as he was in the process of drafting it. Gissing used the miniaturized form to more efficiently calculate the average words per line and page of manuscript, thereby compressing larger scales of text into more measurable/manageable units. Furthermore, as you will see, Gissing’s handwritten form that ostensibly standardized word count per page reflected his ambivalent loyalty and hesitant conformity to the reigning system of the three-volume or triple-decker novel, which, in comparison with other nineteenth-century print forms, relied on amassing large quantities of words as a standard of profitability and intelligibility.

Conventionally, we have been taught that the Victorian compulsion for verboseness and long-form texts was a response to both economic and novelistic trends (think Dickensian seriality). But while Gissing’s adoption of a microscopic handwritten form around 1890 confirms these suppositions, it also uniquely exposes how large-scale forces infiltrated and altered an author’s everyday writing practices. Richard Salmon, among others, has articulated the historical-cultural transition from the Romantic notion of the author as a literary genius to the Victorian phenomenon of the author as a writing professional, but my article highlights how late-nineteenth-century macroeconomic dynamics engendered a comparable expression on the individual level, shifting control over textual forms and sizes from the individual author to the coercive techniques of the publishing industry.

Yet the Gissing microscripts and the history of their subsequent transference into print formats also complicate this ostensibly one-sided transaction. My essay explores how Gissing’s drafts not only conformed to the publishing conventions of the time, but also how they intervened within these very same institutions—self-reflexively calling attention to the material absences usually effaced in the transformation from a private to a public textual format. The archive reveals how Gissing’s New Grub Street, for example, sustains a commitment to the occluded labour of Victorian writers under the reigning triple-decker print economy. Critics have already deemed the novel as semi-autobiographical in its reflection of a writer’s (Gissing’s) struggle to survive as a professional author, but the essay binds the material archive with the narrative context, extending the analysis to the minutiae of Gissing’s writerly practice. Gissing’s microscopic handwriting impeded, to varying degrees, the transformation of his stories into commodities, slowing down or prolonging their time to publication. Gissing’s microscopic archival form bears witness to the print industry’s sway over authorial labour, but it simultaneously acts as a protest to the constraints of the three-volume’s predetermined size and form. Without Gissing’s miniaturized manuscripts, the novel becomes divorced from the material reality of its construction and distribution. My archival analysis refuses to disremember the authorial labour that preceded the novel’s consumption as a commodity. Gissing’s microscript inserts the material constraints of novelistic production and authorial toil upon the commodity-form’s state of fictional amnesia.

For more see: Mier, Sean. “Size Matters: George Gissing’s Microscript and the Late-Victorian Print Market.” Victorian Review, vol. 48 no. 2, 2022, p. 249-269. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/vcr.2022.a900626.