by Meghna Sapui

The first restaurant I ever went to in the United States was the Chipotle on Archer Road in Gainesville, FL. Here, I asked the server to add capsicum and onions to my bowl. At this, the server looked baffled. It occurred to me then that Americans call bell peppers what Indians call capsicum. Understanding (I got my bell peppers) and laughter (I suppose capsicum can sound vaguely sexual) ensued. For an Indian woman with a bowl of rice, beans, and capsicum in a Tex-Mex chain, this was also a good reminder that I needed to get on with my American. Cultural differences can feel particularly immediate and forceful when they intervene in one’s alimentary practices.

But I am hardly the first to notice this—nineteenth-century colonial authors often faced the same predicament. The British empire in South Asia was a diasporic enterprise. A substantial part of this imperial diaspora’s lifeworld was marked by gustatory encounters and exchanges, skewed as they were by the politics of race and empire. Unsurprisingly then, culinary and gustatory representations recur in texts by Anglo-Indians (a term that in the nineteenth century denoted British residents in India). An instance of one such text is George Francklin Atkinson’s illustrated book Curry and Rice (1858) that uses an extended food conceit to talk about India—“her Majesty’s Eastern dominions,” newly minted as such following the Revolt of 1857.

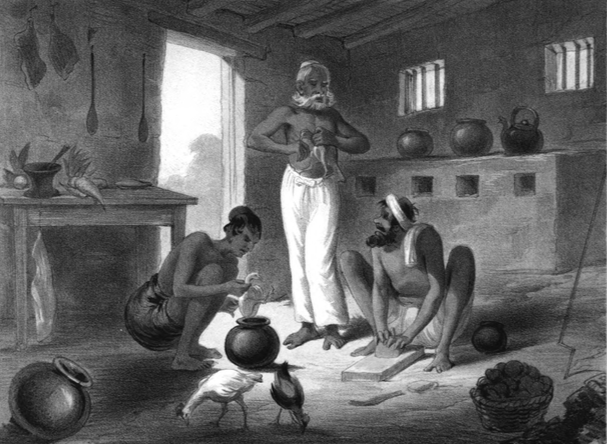

Curry and Rice was written and published in the months following the Revolt, a time when narratives of 1857 constituted the bulk of English-language literature from India. Atkinson, a captain in the Bengal Engineers, a unit of the Company’s army in Bengal , had first-hand experience of 1857. However, Curry and Rice elides any mention of the Revolt. Atkinson declares in his preface that he wishes to provide a reprieve “after all the narratives of horror that have of late fallen upon the English ear.” Thus, the book constitutes of brief vignettes of life in a fictional cantonment town called Kabob. It depicts characters named after Indian foods—Garlic, Turmeric, Huldey, Tamarind, Coriander, and even a Capsicum(!)—and “Indian” scenes, like a tiger hunt, a “burra khanah” (“big dinner”), a cantonment ball, a dinner with the Nuwab of Kabob, and so on.

Atkinson’s choice of medium—an illustrated book—can be attributed to his training as an illustrator, as proficiency with pencil and Indian ink were admission prerequisites at the Company’s military seminary in Addiscombe. His professional and artistic career was also a continuation of a familial tradition. He was one of six children of the renowned Orientalist James Atkinson. Atkinson senior was well known for his English translations of Persian poetry as well as his literary endeavors and friendships with other Orientalists like James Prinsep, Horace Hayman Wilson, and Charles D’Oyly—he even named one of his sons Charles D’Oyly Atkinson! (A little aside: to this day, I have never found an image of any of the Atkinsons except James.) Among James Atkinson’s many translations, the following are some of the most popular ones: the first independent English translation of the Rostam and Sohrāb episode of the Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh, an eventual abridged version of the entire epic, and Nizami Ganjavi’s Laila and Majnun.

While George Francklin’s literary output is not as prolific as his father’s, their works share similar themes. For instance, both write about the peculiarities of the Anglo-Indian experience—James in his melancholic City of Palaces, G.F. in his humorous Curry and Rice. Both write about imperial wars—James wrote and published extensively about his experiences in the First Afghan War, G.F. wrote The Campaign in India, 1857-1858 about 1857. Given his personal and professional background, it is fascinating that following the imperial event that became the boogeyman of the nineteenth-century imperial imaginary, G.F. wanted to write Curry and Rice which was advertised as “the best Christmas gift book.”

Atkinson dedicates Curry and Rice to W.M. Thackeray: “My tiny vessel is to follow in the wake of your big men-of-war.” Thackeray was considered something of an authority on all things Anglo-Indian—born in Kolkata, he thanked Atkinson for writing about his “native country.” Thackeray was also a popular Victorian gourmand who in “Memorials of Gormandizing” declared: “remember that every man who has been worth a fig in this world, as poet, painter, or musician, has had a good appetite: and a good taste.” For a book about India couched in the language of gustation, there could be no more appropriate interlocutor than Thackeray. Thackeray responded to Atkinson’s gesture with gratitude and a warning. He warned Atkinson about the pitfalls of publishing and the harm that a bad review could do, citing the 1852 Times review of The History of Henry Esmond. Curry and Rice in its turnreceived mixed reviews. Some found the timing of this humorous book vexing, appearing as it did so close to the events of 1857. Others reviewing it with its “companion” volume, The Campaign in India, thought it quite appropriate—praising both for their lithographs but finding Campaign much more palatable than Curry and Rice.

Curry and Rice uses the humorous and seemingly innocuous language of food—the residents of Kabob constitute the “curry and rice” dished out on the forty lithograph “plates.” This alimentary discourse, however, becomes politically supercharged when situated within the context of 1857, widely reported by the Anglo-Indian and British press as an affair of peregrinating chapatis, adulterated cartridges, and contaminated salt and flour sold in cantonment bazaars. While at first glance, the hapless Anglo-Indians of Kabob may also seem like inappropriate representational choices at a moment of such unrest, Atkinson’s book might not be as out-of-joint with its historical moment as it claims (or appears) to be. Curry and Rice is generously peppered with apparently jocular racial slurs, marked by the horrifically humorous specter of imperial appetites that miscegenate white bodies and families, and haunted by simian Indian servants who haunt Kabob’s gleaming, though stiflingly hot, dining rooms. All in all, Curry and Rice is a lesson in many things. It shows us how food can be deployed to overwrite imperial politics; how implicit racism is foundation to imperial genres, like Anglo-Indian satire; and how foodways can be useful in interpreting the political stakes and racial ideologies at work in imperial texts.

To read more, see Sapui, Meghna. “The Culinary and the Colonial in G.F. Atkinson’s Curry and Rice.” Victorian Review, vol. 48 no. 2, 2022, p. 225-248. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/vcr.2022.a900625.