by Rebecca Sheppard

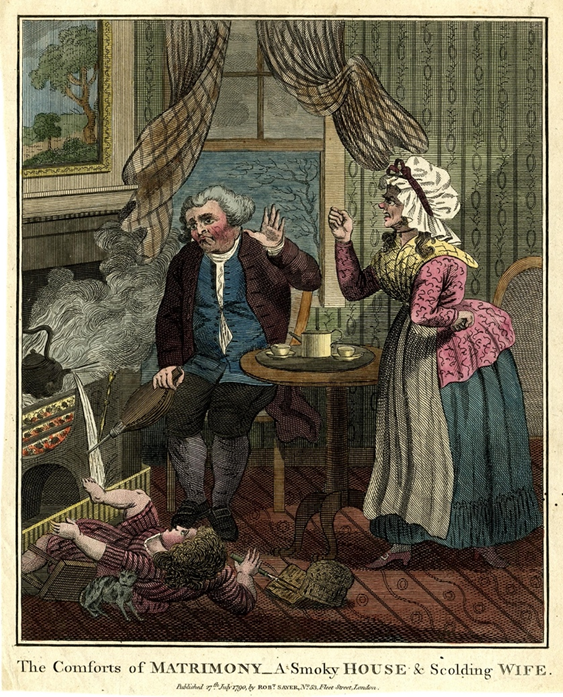

What’s with blaming Helen for her husband Arthur’s increasingly bad behaviour? Going back to the first reviews of Anne Brontë’s Tenant of Wildfell Hall (1848) Helen has been chided for her “self-willed rashness” (“Tenant” [Sharpe’s] 182) and her bad decision “to link herself … [with] a sensual brute” (“Tenant” [Rambler] 65). More recently, literary critics condemn Helen’s “superior attitude” (Jackson 204), “incessant lecturing” (Langland 143), and “special arrogance” (McMaster 355). Was it, though, Brontë’s intention to chastise the wife, or are we meant to take a longer look at the path Arthur has chosen for himself leading to his own demise (and death)?

In the novel, Helen’s diary serves two purposes: to exculpate herself for the crime of leaving her husband (legally, she is at fault) and to serve as a model for Gilbert, whose behaviour is in need of modification. Helen includes a detailed account of her four-year cohabitation with Arthur: an excruciating, monotonous litany of emotional abuses. Arthur’s progressively atrocious behaviour speaks to each objective. There is a rather large qualification to make here, however. Arthur’s violence is in his words and deeds (such as forcing alcohol on his young son and destroying Helen’s paintings); it is not physical. Nevertheless, Brontë asks us to draw parallels between physical abuse (both spousal and Gilbert’s attack on Mr. Lawrence) and Arthur’s immoral conduct. The mid-nineteenth century saw an increase in domestic abuse cases tried in courts of law. There was in the law, concurrently, a newer emphasis on reason and rationality as the standard for cases involving provocation.

Science, and Art, vol. 15, no. 388, 1855, p. 333.

And what do we learn from Arthur? Wildfell Hall was written at a time when crime was seen primarily as a moral failing; individuals with deficient character broke the law. Within the legal domain, individuals were increasingly seen as rational and responsible beings who ought to be held accountable for their decisions. Arthur’s gradual deterioration—both physical and moral—is attributed to the structure of his mind and his alcoholism, both of which were thought to be in an individual’s control. Arthur’s dying words— “Oh, Helen, if I had listened to you, it never would have come to this! And if I had heard you long ago—oh God! How different it would have been!” (TWH 367)—are an acknowledgement that absolves Helen of responsibility for her husband’s decline.

Arthur’s conduct also serves a model. Brontë shows no sympathy for Gilbert’s physical assault on Mr. Lawrence. He acts out while in a passionate state of mind; however, he should have known better. Unlike a “reasonable man,” he has not controlled his emotions, something he must learn to do in order to become a suitable partner for Helen. While Gilbert can and does improve, Arthur has a deteriorating ability to be reasonable. In keeping with the more conservative aspects of the law Brontë, restricts responsibility for one’s actions to include a degree of accountability for one’s past moral deeds. The “moralizing subtext,” which Martin Wiener locates in the law—the “hardly questioned acceptance of strengthening self-discipline, foresight, and reasonableness of the public” (83)—plays out in the novel.

The novel is less of a conduct manual for wives to be less nagging; rather, it is a condemnation of men to behave better in full accordance of the changing nineteenth-century legal standards.

For more see: Sheppard, Rebecca. “”You Have Only Yourself to Blame”: Mind and Reason in Anne Brontë’s: Tenant of Wildfell Hall.” Victorian Review, vol. 48 no. 2, 2022, p. 207-224. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/vcr.2022.a900624.

Bibliography

Brontë, Anne. The Tenant of Wildfell Hall. Oxford UP, 2008.

Jackson, Arlene. “The Question of Credibility in Anne Brontë’s The Tenant of Wildfell Hall.”

English Studies, vol. 63, no. 1, 1982, pp. 198–206.

Langland, Elizabeth. Anne Brontë: The Other One. Barnes & Noble, 1989.

McMaster, Juliet. “’Imbecile Laughter’ and ‘Desperate Earnest’ in The Tenant of Wildfell Hall.

Modern Language Quarterly, vol. 43, no. 4, 1982, pp. 352–68.

“The Tenant of Wildfell Hall.” The Rambler, Sept. 1848, no. 3, pp. 65–66.

“The Tenant of Wildfell Hall.” Sharpe’s London Magazine, July 1848, no. 7, pp. 181–83.

Wiener, Martin J. Reconstructing the Criminal. Cambridge UP, 1990.