By Elly McCausland

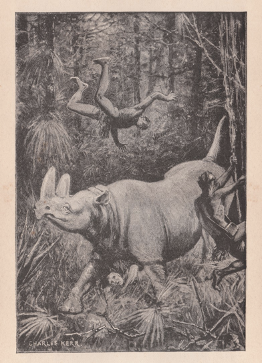

Illustration by Charles Kerr in Rider Haggard, Maiwa’s Revenge; or, the War of the Little Hand (London: Longmans, Green & Co., 1888)

In 2017, children’s author Katherine Rundell published The Explorer, a modern-day adventure novel that would go on to win the Costa Children’s Book Award. The novel follows a group of four children whose plane crash-lands in the jungle after the pilot suffers a fatal heart attack. They stumble upon the ruins of a magnificent ancient city, deep in the heart of the Amazon. Its guardian is a former explorer who has taken it as his life’s mission to protect the ancient city. He has built a jungle canopy to shield it from ‘people surveying the land from the air […] From people looking for El Dorado. From people looking to pack places like this into parcels of stone and sell them to curious ladies and gentlemen in Chelsea for the price of a bus driver’s yearly wages. From people exactly like me’.[1] He is determined to keep the magnificent ruins a secret until human society relinquishes its obsession with dominating and plundering the environment: ‘The time will come, I hope, when the world values people as much as it values land. But for now, we do not need more men in pith helmets marching through the jungle towards us.’[2]

We can read Rundell’s story as ‘writing back’ to the adventure novels of the later nineteenth century, often grouped under the genre ‘imperial romance’ and featuring an all-male band of heroes who venture into the unknown – usually darkest Africa or South America – stumble upon a lost city and escape its inevitable booby traps and hordes of avenging ‘savages’ in order to regale a Victorian reading public with tales of their derring-do. Rundell offers a clear counter-narrative to such tales, with her gruff explorer condemning the activities of colonialist soldiers and the havoc they wrought upon the forest ecosystem. At the end of the novel, its young protagonist Fred grows up to become what the newspapers call ‘A new kind of explorer’ – one who, it is implied, is respectful of the landscape he traverses and aware of his potential impact.[3]

The Explorer situates itself firmly in opposition to what it implies to be the single narrative of exploration that dominated the late nineteenth century: masculinist, colonialist, anthropocentric. It is a narrative often brought to life in the fiction of renowned Victorian adventure writers such as Rider Haggard, Rudyard Kipling and Joseph Conrad, with recent scholarship devoted to identifying the problematic environmental ideologies of these novels in addition to their noted racist and misogynist tendencies. Destruction of animal and plant life is rampant in many of these texts, but gathers relatively little critical attention, overshadowed as it often is by the gratuitous slaughter of native peoples that is also often a key plot feature. Yet it struck me, while reading Rundell’s novel for the first time recently, that the counter-narrative she offers is not a new one, and in fact exists as a haunting sub-text within many of the novels themselves.

Recently, scholars have begun to identify more ambiguity in these texts, and I have attempted to continue this conversation in my article for Victorian Review, ‘“The Game has Gone”: Animal Fantasies and Environmental Realities in H. Rider Haggard’s Imperial Romance’. I argue that we ought to pay close attention to the frequent, detailed depictions of the animal body and native flora and fauna in Rider Haggard’s novels, as these offer clues to a fundamental anxiety that underpinned his depictions of colonial adventure. In Haggard’s writing we can identify a paradox that inflects a large proportion of nineteenth-century imperial romance: adventure relied for its thrills on tempting travellers into the ‘blank spaces’ of the map, but simultaneously acknowledged that those spaces could only retain their appeal if left uncharted. This tendency is evident in multiple examples from the genre – novels by Frank Aubrey, J. Provand Webster, R. D. Chetwode and James Cobban, among others – all of which close with a dramatic incident or accident that sees their explorers unable to return to, or map, the lost worlds at their hearts. We might actually trace the seeds of Rundell’s counter-narrative back to these novels, which, even as they promoted anthropocentric, violent adventure in exoticised locales, were simultaneously haunted by the guilt and anxiety that they might be contributing to the irreversible disappearance of such places. There is little difference, in actual fact, between the stern warnings of Rundell’s explorer and the sentiments of Haggard’s Henry Curtis, over a century earlier:

I have no fancy for handing over this beautiful country to be torn and fought for by speculators, tourists, politicians, and teachers, whose voice is as the voice of Babel […] nor will I endow it with the greed, drunkenness, new diseases, gunpowder, and general demoralisation which chiefly mark the progress of civilisation amongst unsophisticated peoples.[4]

To learn more, see McCausland, Elly. “”The Game Has Gone”: Animal Fantasies and Environmental Realities in H. Rider Haggard’s Imperial Romance.” Victorian Review, vol. 46 no. 2, 2020, p. 235-254. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/vcr.2020.0021.

[1] Katherine Rundell, The Explorer (London: Bloomsbury, 2018), p. 299.

[2] Rundell, The Explorer, p. 301.

[3] Rundell, The Explorer, p. 392.

[4] Rider Haggard, Allan Quatermain (London: Wordsworth Editions, 1994), p. 310-11.