by Katherine Anne Gilbert

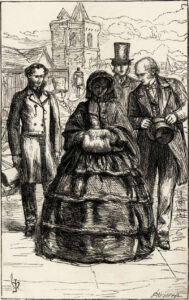

‘Lady Mason going before the Magistrates’. Source: 1981 Dover Orley Farm, ii, p. 96 Hall, AT and His Illustrators, pp. 29-40.

As Victorianists, we often turn to sensation fiction as the genre in which disruptive challenges to social, legal, and gendered structures were narrated in the nineteenth century. Victorian condemnations of sensation fiction are read as traditionalist calls for conservation of the status quo, one in which individuals remain clearly organized into categories that reinforce inequities in class, gender, and wealth. Anthony Trollope’s Orley Farm (1862), however, troubles such easy categorization. Trollope, long considered a consummate realist, tells the story of Lady Mason, the young, second wife of the deceased Sir Joseph Mason, who forges her dying husband’s will to redirect the line of inheritance to her son. Lady Mason is tried–twice—first for forgery and then perjury, and found innocent both times. Yet Trollope, while simultaneously detailing Lady Mason’s crimes, encourages readers not to judge Lady Mason too quickly. How might we read this novel in light of the categories of realism and sensationalism, continuity and disruption, gender and inheritance? And, how might we understand forgery in this light, a crime that brings to the fore concerns about how to classify something as original and true or an imitation and dishonest?

I suggest that it is not the acts of crime that bring together Trollope and sensation fiction in Orley Farm, but a near obsession within the novel with forms of classification themselves. Strikingly, this fixation on classification permeates the novel from the more sensational (is a beautiful Lady capable of crime?), to the mundane (is a lawyer a professional or a commercial man, and should he be allowed in the commercial men’s lounge at a traveler’s Inn?), to class and race (can Lady Mason’s son, Lucius, devise a new system of classification of humans, one that intertwines an analysis of the structures of languages with a racial mapping through history?). Building on the work of others such as Susan David Bernstein, who demonstrates that sensation fiction’s interest in classification intersects with the publication of Darwin’s Origin of the Species, I trace the ways that classification, and threats to it, appear repeatedly in Orley Farm, and argue that it is this interest in forms of classification and their permeations that the novel shares most forcefully with sensation fiction. Taking up Marlene Tromp’s recent problematizing of our own contemporary interest in classifying realism and sensation fiction even now, I then ask, what does it mean to contextualize Lady Mason’s acts as realistic or sensational? Whose stories, as Tromp suggests, are presented to us as within the realm of the likely and the everyday, and what are the political stakes of such classifications?

To read more see Gilbert, Katherine. ““I Wrote Them All”: Forgery and Forms of Classification in Trollope’s Orley Farm.” Victorian Review, vol. 45 no. 2, 2019, p. 307-323. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/vcr.2019.0061.