by Melanie V. Jones

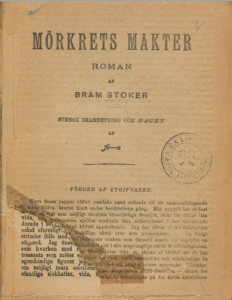

Recently, the field of translation studies was shaken to its core. The Icelandic Makt Myrkranna (Powers of Darkness, 1901), long believed to be a faithful translation of Bram Stoker’s 1897 original, in fact contains serious deviations from the source text, creating a radically different work. Researcher Hans Corneel de Roos initially suggested that Stoker may have collaborated with the translator, Validimar Ásmundsson, to produce an alternate version of the classic vampire tale. Yet that supposition was quickly overturned by the discovery of an even earlier “translation,” the Swedish Mörkets Makter (Powers of Darkness, 1899), with striking links to the Icelandic text. De Roos now believes that both these texts and their prefaces — signed by a “B.S.” once assumed to be Bram Stoker — are in fact fantastic forgeries.

This blatant co-opting of textual bodies, and their ability to remain hidden for over a century, are just the most recent in a long history of the vampire’s connection to fraud, plagiarism, and literary piracy. As these creatures began to embody contemporary anxieties regarding origin and authenticity, nineteenth century authors began to freely use vampiric literature as a cover to engage in faux-translations, misattribution, literary piracy, and outright forgery.

“Dracula or Draculitz? Translational Forgery and Bram Stoker’s “Lost Version” of Dracula” examines how Makt Myrkranna and Mörkets Makter exploit this trend on both a thematic and formal level. Both texts are fascinated with the vampire as a symbol of the very forgeries their works carry out. Their version of Dracula, “Draculitz,” can concoct much more elaborate and ultimately more successful frauds, and his vampiric doubles no longer need to be turned by him one by one — they proliferate the text, swapping identities at will. What might these acts of forge/ing tell us about the role of the translator as vampiric creator? Do these adaptations suggest that the fake, the stolen, and the copy are necessary to assert, or may even need to precede, the concept of an original?

To read more, see Katy Brundan, Melanie Jones, and Benjamin Mier-Cruz. “Dracula or Draculitz?: Translational Forgery and Bram Stoker’s “Lost Version” of Dracula.” Victorian Review, vol. 45 no. 2, 2019, p. 293-306. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/vcr.2019.0060.