by Alexis Easley

On October 5, 1881, Inspector Henry Moore arrived at the Langham Hotel in response to a suicide threat. He found a forty-four-year-old baronet, Sir Gilbert Edward Campbell, sitting in room 170, a bottle of poison at his side. “It is perfectly impossible for me to live,” Campbell told the inspector, and then explained that he fully intended to take his own life the next day at noon if the Alliance Assurance Company did not give him an advance upon his life insurance policy. He was broke and homeless and needed just enough money to get him “through the bad season.” The inspector apprehended Campbell and took him to the Marylebone Police Station, where he was charged with “being an insane person and not under proper control.” It soon became clear that Campbell’s supposed suicide attempt was a money making scheme. Indeed, his appeal to the Alliance Assurance Company had been a thinly disguised attempt at blackmail. His death would be a “bad thing for the Alliance,” he threatened in a money-begging letter to the company. Once in police custody, Campbell made no further suicide threats and acknowledged that he “had made a fool of himself.”

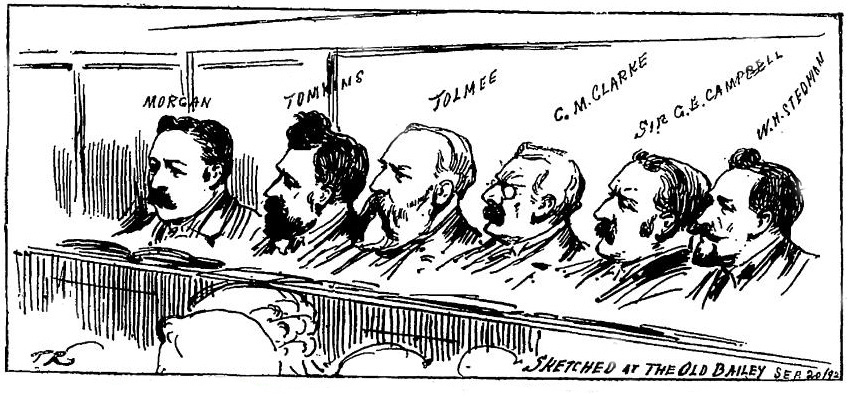

This was just one of many criminal episodes in the life of Sir Gilbert Edward Campbell. In October of 1892, he was convicted of conspiring to defraud the public by co-managing a bogus literary agency that offered fake diplomas, promises of publication, and editorial assistantships in exchange for cash payments. The agency was particularly successful in fleecing amateur writers, who paid for their manuscripts to be read and published only to find weeks later that the agency had closed shop and its managers were nowhere to be found. The case revealed the dark side of the literary marketplace, where unscrupulous men such as Campbell could capitalize on the oversupply of literary aspirants, defrauding them of their money and creative work.

What made Campbell’s story unique was the fact that he was also a writer, editor, and translator. As a translator, he was responsible for introducing cheap editions of the works of French writer Emile Gaboriau, today acknowledged as the father of the detective novel genre. Campbell also published his own detective stories in Christmas annuals and wrote a handful of mystery novels, including The Mystery of Mandeville Square (1888) and The Vanishing Diamond (1890). In 1890, he became editor of Lambert’s Monthly, which published serialized sensation novels and detective fiction. At the same time that Campbell was translating, writing, and editing detective fiction, he continued to pursue a life of crime.

Campbell’s exploits probably would have gone unpunished if it were not for Henry Labouchère’s weekly newspaper Truth, which investigated the case and transformed it into a gripping serial. Truth was of course complicit in the cases it investigated since it relied on a steady flow of crime narratives to sell papers. It also engaged in editorial practices focused on disguise and manipulation that echoed the actions of the criminals it claimed to criticize. On the one hand, Truth seemed to construct a clear line between the heroic editor and the aristocratic literary villain. Yet it also indirectly revealed affinities between literary criminals and the journalists who investigated their crimes.

To read more see, Alexis Easley, “The Man of Letters as Criminal: Sir Gilbert Edward Campbell and Henry Labouchère’s Truth.” Victorian Review, vol. 45 no. 2, 2019, p. 253-270. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/vcr.2019.0058.