by Aubrey Plourde

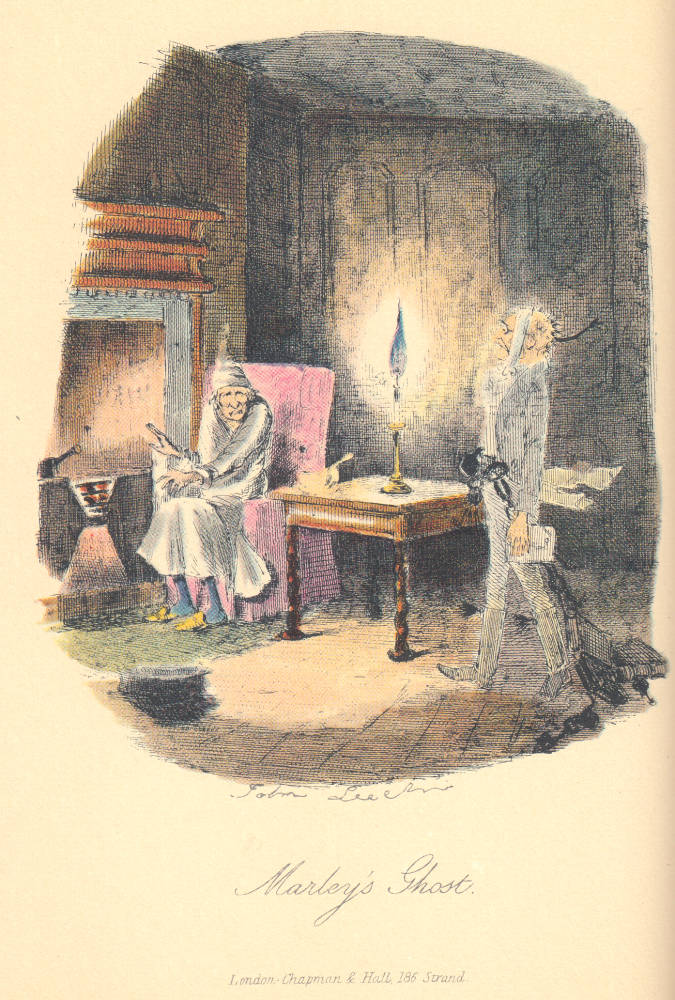

As part of his campaign for education and against child labor, Charles Dickens imagined A Christmas Carol as an antidote to the poverty he saw on his visit to Manchester. The book, he believed, would present the plight of the poor in a way his readers could understand, and it would motivate them to do something about it. The book was so phenomenally popular from the moment it was published in December 1843 that it earned Dickens the title “the Man Who Invented Christmas.”

The extent to which A Christmas Carol really did accomplish the social benefits Dickens hoped for was up for debate. Some readers received it as a “new gospel,” supplement or substitute for the scripture that was, perhaps, losing its mass appeal. Others, like Ruskin, bemoaned the Carol’s lack of real sacred truth. While lay readers were drawn in by Scrooge’s conversion, others, including many of its critics, have seen it as a cheap trick, an enchanting but flimsy tale of a hastily-reformed moneyman.

But the novel itself is, in some ways, about enchantment in reading. In my article in “‘Another Man from What I Was’: Enchanted Reading and Ethical Selfhood in A Christmas Carol,” I explore the textual relation between enchantment and ethics in A Christmas Carol. Typically, “Scrooge,” evokes something along the lines of “cheap.” Stingy, miserly, close-fisted, ungenerous, Scrooge has become the mascot of the one-percent. But his criminal frugality, is born of his suspicion. My essay is built on a small premise: Scrooge is a miser because he is a skeptic. If he hoards his wealth and resources, he does so as an outgrowth of his insistence on a materialist epistemology. In fact, he’s a lot like a skeptical reader, taking in the ghosts’ vignettes at first with a guarded sense of suspicion—alert for enchanted humbugs that might hoodwink him—and, I show, ultimately with a performed suspension of disbelief.

The ethical change of A Christmas Carol—a change Dickens explicitly envisioned as not just the reform of Scrooge but in fact the transformation of an entire generation—requires a change in worldview, in standards of truth, and methods of interpretation. In this novel, the imagination is not precisely a better way of getting at truth than materialist logic, calculation, or science—but in fact becomes a method by which epistemologies—visions of past and present, ways of reconciling the self and the other—could be imagined to coexist.

To read the full article in the Victorian Review 42.3, click here.