By Alison Hedley

In Summer 2018, the Ryerson Centre for Digital Humanities launched the website for the Yellow Nineties Personography, a biographical database of persons who contributed to a number of little magazines produced in Britain at the fin de siècle, as documented by the Yellow Nineties Online. The website is a culmination (but not the final output) of many years’ research and development. One of the most theoretically challenging aspects of this work has been developing the Personography’s domain model—a formal representation of its organizational structure which describes the Personography’s knowledge domain by assigning the data classes, attributes, and rules. The taxonomy of Victorian occupations that constitutes a specific sub-structure of this ontology illustrates how digitally documenting the Victorians can enhance our recognition of the possibilities and limitations inherent in both historical and contemporary models for structuring cultural knowledge.

Limits of Twenty-First Century Information Modelling Practices

The Personography is a linked open data (LOD) project: its data, which are available for anyone to download and use under an open access license, include links to related datasets on the Semantic Web, such as the Virtual International Authority File. Our feminist humanities praxis informs how the Personography team implements the principles of linked open data. The project’s best practices balance three priorities: maintaining the contextual, contingent nature of historical data about persons and artistic works; implementing an intersectional feminist ethic that speaks back to the socio-political hegemony evident in the historical record; and tempering these humanities values with pragmatic computational flexibility.

One of the guiding principles of LOD is the interoperability of domain models. Structural similarity between two datasets makes it easier for a human user or machine to navigate between both sets at the same time, interpreting them in relation to one another. Interoperability makes it possible to find information about the same subject across different linked datasets or identify wider contexts in which to situate that subject to understand it holistically.

In keeping with our best practices, our domain model combines categories from other linked data ontologies on the Semantic Web with custom-built classes and attributes. A facet of this work that has been particularly challenging for us is the development of a taxonomy of Victorian occupations for our model. We found existing occupations taxonomies inadequate for our database. To the best of my knowledge, no published linked open ontology faithfully documents the spectrum of late-Victorian British vocations. Established ontologies developed for linked open cultural heritage data, such as the Getty Research Institute’s linked open vocabularies, are too contemporary for our purposes. For example, Getty’s distinction between “white collar” and “blue collar” workers is similar, but not identical, to the Victorian distinction between professionals and tradespersons; using the Getty terms would erase some of our data’s historical specificity.

The Personography team decided to look to nineteenth century models to develop a historically appropriate structure for describing occupations. We eventually drew on the classification system developed for the Census of England and Wales, 1881 and 1891, which offers perhaps the most comprehensive record of late-Victorian occupations available in both the late nineteenth century and our own historical moment. Indeed, Charles Booth’s Life and Labour of the People in London (1892-1897), itself a famously extensive survey of the socio-economic landscape of urban Britain, adopted the organizational logic of the 1891 Census to structure its volume on industry. Like any knowledge model, though, the Census occupations taxonomy imposes a rubric that prioritizes some features of information at the expense of others. Understanding the limitations of the Census model requires contextualizing it within Victorian culture.

Limits of Victorian information modelling practices

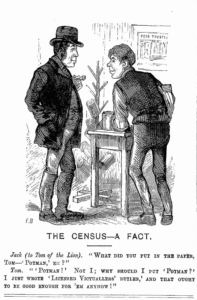

The occupations taxonomy’s reception on Twitter drew my attention to Victorian cultural assumptions inscribed in the Census system. I published a snapshot of the taxonomy that I had diagrammed with Coggle, thinking it would generate some interest among a small coterie of Victorian data nerds like me (figure 1). To my surprise, the image circulated widely—by academic Twitter standards—and sparked a generative conversation about a disparity between the Census-based taxonomy and the socio-economic divisions that shaped the cultural landscape of Victorian Britain. The conventional hierarchy of occupations took as its guiding principle the type and level of education needed to attain different vocational positions. Education is traditionally an essential marker of class, itself a prominent feature of British social relations.

The Census categories reject this education-based, social hierarchy of occupations. For example, although late-Victorian publishers and librarians occupied a similar socio-economic rank to the well-educated journalists and authors in the professional class, they are assigned to an industrial sub-class in the Census taxonomy—Books, Newspapers, and Maps—because their work focused on print media. Within the larger Industrial Class, publishers and librarians are on the same occupational plane as members of the Domestic Class, such as gamekeepers and charpersons, a parallel that would have shocked most Victorians. Indeed, as Matthew Woollard has noted, the Census taxonomy of occupations was criticized for this very reason when it was first implemented in the late nineteenth century (19).

That the taxonomy largely sets aside British class distinctions is useful for the purposes of the Personography. Using the Census categories, we can document Victorian occupations using Victorian-specific terms without imposing the socio-economic hierarchy that made rich, well-educated persons more visible and poorer, less prestigiously educated persons more obscure in the historical record. Increasing the visibility of such marginalized persons is consistent with our project’s aims.

While using the materialist system of the late-Victorian Census has advantages, we recognize that we have traded one ideologically inflected framework for another. Rather than prioritizing socio-economic distinctions, the Census taxonomy of occupations prioritizes aspects of occupation type that are pertinent to Victorian scientific and industrial knowledge domains. The Census groups vocations by material outputs, which range from entertainment to newspapers and products made of animal bone. This materialist orientation reflects the industrial ethos of the era. More importantly, it attests to the Victorian imbrication of empirical positivism and bureaucracy (Peters 14). As an approach to producing knowledge, bureaucratic positivism had implications for how the state, cultural institutions, and Britons themselves understood persons in relation to society. Statistical practices made possible through mechanisms such as the Census used quantitative aggregation to make the unseen visible and develop generalizable principles about human behaviours (Peters 14). Giving shape to a normalized national body through its techniques of aggregation, the Census exemplifies the data-driven approach developed by Victorian political economists and agents of the state to manage and intervene in population life.

This approach had many advantages, but it tended to flatten difference and deracinate the real experiences of Britons as abstract data points, making some kinds of information about persons invisible. To uncritically adopt Victorian statistical practices such as the Census occupations system is to recapitulate the values that shaped those practices. However, the Personography seeks to recuperate marginalized biographical knowledge, not contribute to its erasure for the historical record. For us, then, the knowledge model offered by the late-Victorian Census has its limitations, just as the models offered by linked open ontologies on the Web have theirs.

Modelling the Past in the Present

So how do we use Victorian classification practices without endorsing their ideological precepts? This question has relevance beyond the Census occupations taxonomy. Many digital humanities methods that incorporate practices of classification and quantification have a Victorian history. Indeed, personography itself originates in prosopography, a historiographic method developed in the 1890s to study historical populations in aggregate. Can we incorporate such approaches of data modelling without reinscribing their latent politics?

This question is one of the core preoccupations of digital humanities methodology, and every computational practice that involves disambiguating our messy humanities knowledge demands a new approach to answering it. When structuring humanities data, we must attend to the historical contexts and contingencies that might be thrust into the spotlight or pushed offstage depending on how we model the information. In sharing our research, we must highlight the limitations, as well as showcasing the revelations, afforded by the model(s) we’ve chosen. Accordingly, scholars continue to explore ways that we might deploy techniques that use a model’s primary expressive modes in order to draw users’ attention to how the model itself is interpretive.[1] Such an approach may not be feasible within all realms of DH scholarship, but every DH research creation can—and should—include a critical apparatus that describes its history of production. Accordingly, an essential aspect of the Y90s Personography website is the commentary on our methods and models that appears in many portions of the site. This aspect of our scholarship draws users’ attention to how our modelling process is interpretive, with its own unique contexts and limitations. We encourage users not only to explore the Victorian past using digital tools, but also to recognize the complex Victorian past of our digital methods for producing knowledge.

Alison Hedley (orcid.org/0000-0002-4236-0763) is a SSHRC Postdoctoral Fellow at the McGill University .txtLab and editor of the Yellow Nineties Personography. She has published in Victorian Periodicals Review and the Journal of Victorian Culture. Alison is completing a book about popular illustrated magazines in the new media landscape of fin-de-siècle Britain; her postdoctoral research investigates information visualization in popular Victorian journalism.

[1] For example, Johanna Drucker explores how we might use visual features of a graphical interface to draw attention to this model’s status as a hermeneutic device, conditioned by its developers to have distinctive affordances and limitations (“Non-Representational Approaches”).

Works Cited

Drucker, Johanna. “Non-Representational Approaches to Modeling Information in a Graphical Environment.” Digital Scholarship in the Humanities, vol. 33, no. 2 (2018): pp. 248-63. DOI:10.1093/llc/fqx034.

Peters, John Durham. “Information: Notes Toward a Critical History.” Journal of Communication, vol. 12, no. 2 (1988): pp. 9-23. Scholars Portal, DOI:10.1177/019685998801200202.

Woollard, Matthew. “The Classification of Occupations in the 1881 Census of England and Wales.” History and Computing, vol. 10, no. 1 (1998): pp. 17-36. EBSCOhost, DOI:10.3366/hac.1998.10.1-3.17.

I find the extremely atrophied ‘domestic’ branch rather curious, considering the number of subdivisions elsewhere… and also that none of the branches here offers an analogue for the numbers of people engaged in them. Taken from that point of view, tobacco is as extensive as domestic service/office and other services, which cannot be right.

How does this graphic show the division of labour between the sexes, or is that a non-topic??

Does it simply reproduce the atrophied Victorian notion of what ‘work’ women did, or does it compound it? I do not see these matters addressed in the accompanying text.

If the graphic were to equate numbers counted and gender in each occupation with some method of portraying these, we might be able to see just how numerically important the domestic was, as against the tiny numbers in other branches/occupations (auctioneers, for example) and how gender-exclusive many occupations were.

This is a helpful chart as far as it goes, but it doesn’t go near far enough to be revealing of very much. Keep at it, please!