Today’s guest blogger is Jennifer R. Henneman, who holds a PhD in Art History from the University of Washington, and is Assistant Curator of Western American Art at the Petrie Institute of Western American Art at the Denver Art Museum. Jennifer’s interdisciplinary transatlantic research, which has taken her from the wilds of the American West to the cosmopolitan streets of London, reflects her own upbringing on a cattle ranch in Montana and her interest in the dominant cultural and artistic spheres of the late Victorian era. In addition to creating exhibitions for the Denver Art Museum, Jennifer currently pursues a book project on the 1887 American Exhibition in London.

My daily walk to work at the Denver Art Museum includes a southward view down Broadway, one of Denver, Colorado’s primary north-south thoroughfares. Above the westward skyline rises “Jonas Bros / Furs” in red neon letters. A legacy of the city’s 1920s urban landscape, the sign towers over the art deco building out of which the Denver branch of the Jonas Brothers’ taxidermy and fur company operated for much of the 20th century.[1]

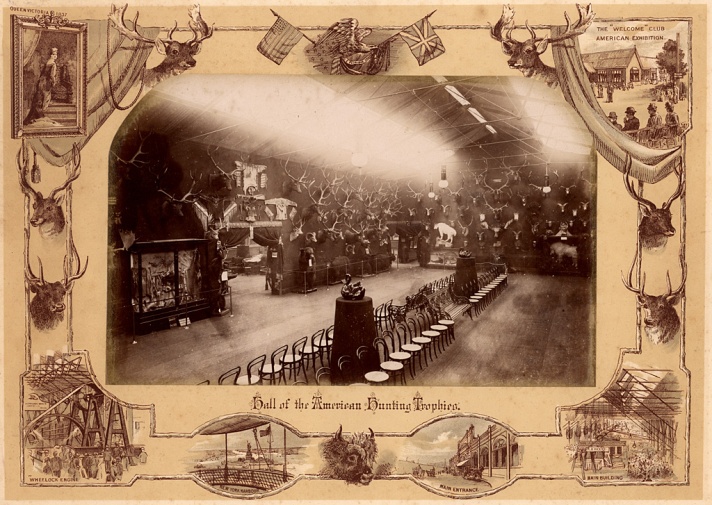

The success of the Jonas Brothers’ firm was built on a 19th century tradition of big game hunting in the Colorado Rockies and its associated industry, taxidermy, which reached highest popularity during the latter part of that century. Lately, taxidermy is much on my mind as I consider the ramifications of North American hunting trophies exhibited within the Fine Arts Galleries of the American Exhibition in London of 1887, an event best known for hosting Buffalo Bill’s Wild West on its first tour abroad. I am interested in the strangeness of the Fine Art Galleries, in which the moulded forms of animal bodies held court adjacent to over a thousand works of American art. Hunted by British sportsmen in North America, these trophies reinforced active British participation in America’s westward expansion, and remind me of the imperial footprints left by such hunters in my current Colorado vicinity.

Buffalo Bill Center of the West (MS6.3829.021).

Available here.

Although a curator of western American art – which broadly includes artworks that focus on the landscapes, people, and wildlife of the American West – in a city that only recently shed its cow-town roots, I am surrounded by a history in which British Victorians played an active role. During the middle decades of the 19th century, Englishmen, Irishmen, and Scotsmen sought land and health in the American West. Many found the high and dry air of Colorado a useful antidote to the scourge of consumption.[2] If not traveling for pleasure or health, British immigrants from diverse socio-economic backgrounds moved west hoping for opportunity in mineral wealth and as purveyors of the goods and services needed by boom towns. Some wealthy families pushed their troubled sons westward with remittances, while younger sons from aristocratic families sometimes went west in search of opportunities they did not have at home.[3]

Windham Wyndham-Quin, the 4th Earl of Dunraven and Mount-Earl (1841-1926), presents an excellent case study for considering the role of wealthy British sportsmen in “taming” the American West. According to his 1880 essay “A Colorado Sketch,” the rumor of plentiful game first led him in 1872 to Estes Park, located about 65 miles northwest of Denver. Over the course of a few years, Dunraven had obtained control of nearly 15,000 acres around Estes Park. Reveling in the grandeur of the region’s geography and abundance of its wildlife, in his 1880 essay Dunraven points out that any geologist, geographer, botanist, mineralogist, man of science, and man of art would find ample interest in the expansive Rocky Mountain region.

Dunraven’s attention to natural detail in his writing is mirrored in the painting style of German-born American artist Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902). In 1876 (and for a whopping $15,000), Dunraven commissioned Bierstadt to paint his favorite hunting ground. The result — Bierstadt’s large and highly detailed Estes Park — hung in Adare Manor, Dunraven’s family seat in County Limerick, Ireland, until the early 1950s, when it was purchased by the Denver Public Library to become one of the most historically significant artworks in Denver. Now generously on long-term loan to the Denver Art Museum, Bierstadt’s Estes Park commands one of the foremost sightlines in Backstory: Western American Art in Context, a collaborative exhibition between the Denver Art Museum and the History Colorado Center.

American, born in Germany, 1830–1902

Estes Park, Long’s Peak (1877)

Oil on canvas

62 x 98 in.

Denver Public Library, Western History Department, 35.2008

Dunraven published tales of his hunting adventures in the American West in The Great Divide (1874) and in his 1922 memoir Past Times and Pastimes. He also contributed trophy mounts to the 1887 Hall of American Trophies at the American Exhibition in London. Displayed in country homes and castles, mounts such as these, and paintings such Bierstadt’s Estes Park, reveal the overlap between American westward expansion and British imperialism via the active participation of wealthy international sportsmen.[4]

Static taxidermic trophies downplay the violence of hunting to focus on the minutia of specimens, thereby demanding scrutiny and comparison perfectly enabled by the ordered, linear display of trophies at the American Exhibition. To an extent, this kind of looking resonates with how many Victorians approached landscape painting, giving particular attention to natural, geological, and climatic specificities. Landscapes of the American West commissioned by British patrons and/or exhibited in Britain underscore Victorian curiosity in a relatively unexplored land that could be enjoyed as an escape from industrial life, but which also held great promise for replaying an imperial story that, particularly into the late-19th century, many Britons wished to see reaffirmed.

Buffalo Bill Center of the West (MS6.3829.022).

Available here.

[1] The Jonas Bros Fur Company was founded in 1908 by Coloman Jonas, who was originally from Budapest, Hungary. The company is still in existence but now operates out of a building in northeast Denver. See also an unpublished autobiography by Coloman Jonas, compiled by Helen Jonas Johnson, The Jonas Story: From ‘Stuffing’ to ‘Sculpturedermy’ (Denver: Jonas Brothers, c.1983) at the Stephen H. Hart Library and Research Center at the History Colorado Center.

[2] For example, note Isabella L. Bird’s reference to Colorado as “the most remarkable sanatorium in the world.” See A Lady’s Life in the Rocky Mountains (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1879), 48. See also the Earl of Dunraven’s 1880 “A Colorado Sketch” (here quoted from Appleton’s Journal: A Magazine of General Literature), in which he writes “The climate is health-giving… giving to the jaded spirit, the unstrung nerves, and weakened body, a stimulant, a tone, and a vigor that can only be appreciated by those who have had the good fortune to travel or reside in that region” (437).

[3] See Monica Rico, Nature’s Noblemen: Transatlantic Masculinities and the Nineteenth-century American West. Lamar Series in Western History. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013.

[4] See Greg Gillespie, “‘I Was Well Pleased with Our Sport among the Buffalo’: Big-Game Hunters, Travel Writing, and Cultural Imperialism in the British North American West, 1847-72,” The Canadian Historical Review 83.4 (December 2002): 555-584.