by Tara MacDonald

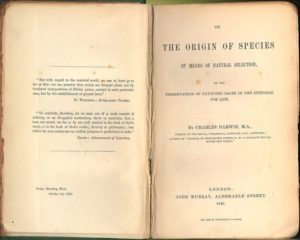

This post begins with an observation: a number of very important books were published in England in 1859. John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty appeared in February, followed by Alexander Bain’s The Emotions and the Will in the spring, and Charles Darwin’s Origin of the Species and Samuel Smiles’s Self-Help in November. This seems striking to me, but is it? I’m tempted to see these publications as part of some kind of ‘cultural moment.’ If anything connects these disparate books, it might be an interest in free will. They all grapple with what it Bain, a prominent Scottish philosopher, calls the “Free-will controversy.”Darwin, for instance, stresses the manner in which the lives of humans (and animals) are dictated by unconscious habitual actions that are often “in direct opposition to our conscious will!” In contrast, Smiles’s, in what is arguably the first modern self help book, emphasizes the power of individual determination: “It is will, – force of purpose, – that enables a man to do or be whatever he sets his mind on being or doing.” Mill too argues for the value of individuality. Using language that recalls the period’s advances in industrialism, he notes, “A person whose desires and impulses are his own … is said to have a character. One whose desires and impulses are not his own, has no character, no more than a steam-engine has a character.”

This post begins with an observation: a number of very important books were published in England in 1859. John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty appeared in February, followed by Alexander Bain’s The Emotions and the Will in the spring, and Charles Darwin’s Origin of the Species and Samuel Smiles’s Self-Help in November. This seems striking to me, but is it? I’m tempted to see these publications as part of some kind of ‘cultural moment.’ If anything connects these disparate books, it might be an interest in free will. They all grapple with what it Bain, a prominent Scottish philosopher, calls the “Free-will controversy.”Darwin, for instance, stresses the manner in which the lives of humans (and animals) are dictated by unconscious habitual actions that are often “in direct opposition to our conscious will!” In contrast, Smiles’s, in what is arguably the first modern self help book, emphasizes the power of individual determination: “It is will, – force of purpose, – that enables a man to do or be whatever he sets his mind on being or doing.” Mill too argues for the value of individuality. Using language that recalls the period’s advances in industrialism, he notes, “A person whose desires and impulses are his own … is said to have a character. One whose desires and impulses are not his own, has no character, no more than a steam-engine has a character.”

And Bain’s entire book is a study of will as it relates to human feeling. Historian Thomas Dixon has argued that the use of the term “emotions” as a major psychological category has only existed for about 200 years, citing Thomas Brown’s 1820 Lectures with developing our modern terminology (138). Bain does not take his audience’s awareness of the term for granted, offering a definition of emotion as “the name here used to comprehend all that is understood by feelings, states of feeling, pleasures, pains, passions, sentiments, affections.”

I’m currently working on a project on Victorian sensation fiction, a genre that arguably begins in earnest in England around this time (I could say much more about how sensation novels were actually published in the UK and American in the 1850s but let’s play along), so I’m intrigued by the timing of these publications. What makes free will and “states of feeling” such a keynote of 1859, in fiction as well as other forms? In the introduction to my book, I’ll take a stab at answering this. For now, I’ll simply suggest that this focus seems to be a response to various cultural and technological changes: humans now had to demonstrate what made them distinct from both animal and machine, and a likeness to either might suggest that our behaviors are more instinctual or mechanical than we’d like to think. I am not the first to make such links. In an article from 2001, Susan David Bernstein specifically linked Origin of Species with The Women in White, noting that both “Darwin and serialized scandalous novels of the decade” possessed “an underlying anxiety about ambiguous boundaries” (250-1).

More recently, in a 2014 article in Victorian Periodicals Review, Linda K. Hughes stresses the virtues of “moving ‘sideways’” through Victorian print forms, of exploring “spatio-temporal convergences in print culture” (1-2). While Hughes specifically tackles periodicals and print culture, she also implies that it can be productive to examine very different texts that may all have appeared in a given year or time period and to note what connections might appear between them. Exploring this “interactivity”, she writes, has implications for the field of Victorian studies as well as for our pedagogy since “it undermines tendencies to see canonical literature as a unitary or unilateral form of cultural authority and invites students to consider a phenomenon similar to some of their own experiences of mass culture” (5, 6).

And of course many have taken up these ideas in their pedagogy and scholarship. Robyn Warhol’s wonderful Reading Like a Victorian site allows you to read “stacks” of Victorian serial novels and see what other texts were published around the same time. In the V21 Collective’s Syllabus site, you can find Ryan Fong’s course (similarly called Reading Like Victorians), which focuses on “a period of twenty-two months between 1846 and 1848.” In 2013, the theme for the NVSA conference was a single year, 1874. Their CFP asked:

What does the close examination of a single year—a year literally picked out of a hat by the program committee rather than chosen for its significance—reveal about the relationship between dates that “matter” in Victorian Studies and dates that do not? Is the calendar year a significant unit of time or useful organizational framework for our exploration of the Victorian period as a whole? How is our understanding of annual publications, commemorations, and other yearly events and forms changed when we concentrate on a single occurrence of each? In 1874 S. O. Beeton’s Christmas annual Jon Duan sold 250,000 copies in three weeks, vastly outperforming Thomas Hardy’s Far from the Madding Crowd. Which, then, is the “major” text under the rubric of our conference? How does our sense of the canonical and non-canonical shift as a result of such micro-periodization?

Hughes and others are still asking and responding to similar questions. The fact that I have found similar investments in a range of texts in this close time period suggests to me that Mill, Bain, and, yes, popular Victorian sensation writers are worth examining alongside one another. Have you experimented with yearly projects or conferences or classes? What other benefits (or limitations) might such kind of work enable?

Works Cited

Texts cited by Bain, Darwin, Mill, and Smiles can all be found at either Project Gutenberg or Archive.Org.

Bernstein, Susan D. “Ape Anxiety: Sensation Fiction, Evolution, and the Genre Question.” Journal of Victorian Culture 2 (2001): 250-271.

Dixon, Thomas. From Passions to Emotions: The Creation of a Secular Psychological Category. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2003.

Hughes, Linda K. “SIDEWAYS!: Navigating the Material(ity) of Print Culture.” Victorian Periodicals Review 47.1 (2014): 1-30.