[Reposted from the Floating Academy]

This week’s guest blogger, Frederick A. King, is a part-time faculty member of the Department of English and Cultural Studies at Huron University College. His research looks at late-Victorian Aestheticism and Decadence in relationship to textual studies and queer theory.

Cover of The Pageant, 1896

I’m currently preparing a digital edition of the aesthetic periodical, The Pageant (1896-97), for The Yellow Nineties Online, a project prepared in collaboration with the Centre for Digital Humanities at Ryerson University and overseen by Jason Boyd, Dennis Denisoff, and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra. This understudied annual, with only two volumes, has a lot in common with better-known aesthetic periodicals such as The Yellow Book or The Dial. It was edited by Gleeson White and Charles Shannon, and features work by many of the names associated with British Aestheticism, including Michael Field (Katherine Bradley and Edith Cooper), John Gray, Laurence Housman, and Shannon’s lover, the designer Charles Ricketts.

For those unfamiliar with the fantastic work of Charles Ricketts, he was a book designer, publisher, stage and costume designer, a sketch artist, a painter, a mentor to, and collaborator with many of his fellow Aesthetes of the 1890s. For literary scholars, his best known works are his book and typographical designs and illustrations for Oscar Wilde’s The Sphinx (1894), and John Gray’s poetry collection, Silverpoints (1893), published by John Lane and Elkin Mathews at the Bodley Head. Ricketts also published the occasional periodical The Dial through his own Vale Press with his partner, Charles Shannon, himself a busy artist.

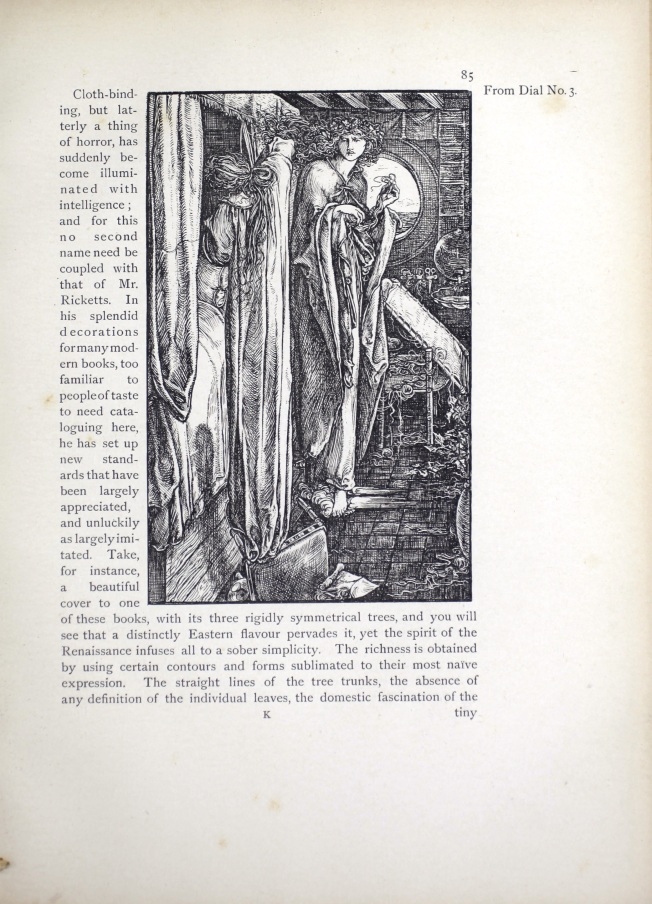

Ricketts wood-cut original published in the third volume of The Dial. Sourced here from Gleeson White’s essay on Ricketts’ work in wood-cut designs.

I discovered Ricketts’ work through my study of Wilde, Gray, and other Aesthetes and Decadents of the period, and found through my research that Ricketts’ collaborative influence actually changed literature. Projects came to Ricketts because of who he knew. When Wilde and Ricketts collaborated on The Sphinx, Wilde extended his poem in order to suit Ricketts’ design and use of space. Ricketts was Gray’s mentor and Wilde asked him to design Silverpoints for the young poet. When Wilde went to the Bodley Head and recommended the pairing, it was Ricketts’ potential design work that convinced Lane and Mathews to publish the book of poems.

Building on these discoveries, I’ve become interested in Ricketts’ work for The Pageant, and in the ways the periodical repositions British Aestheticism outside of its own brief moment of influence in the 1890s, and into conversation with the history of European print culture with roots in the Italian Renaissance. The periodical features numerous critical essays and reproductions of artworks by British and European’s artists whose work influence British Aestheticism. For example, it features the artwork of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, whose medievalist work as a leading member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was a major influence on the Aesthetes; and Gustave Moreau, a Decadent French Symbolist whose “Salome” paintings were also incredibly influential on British Aestheticism. While Aestheticism was intimately connected to British culture, what The Pageant celebrates is the movement’s cosmopolitan sense of history.

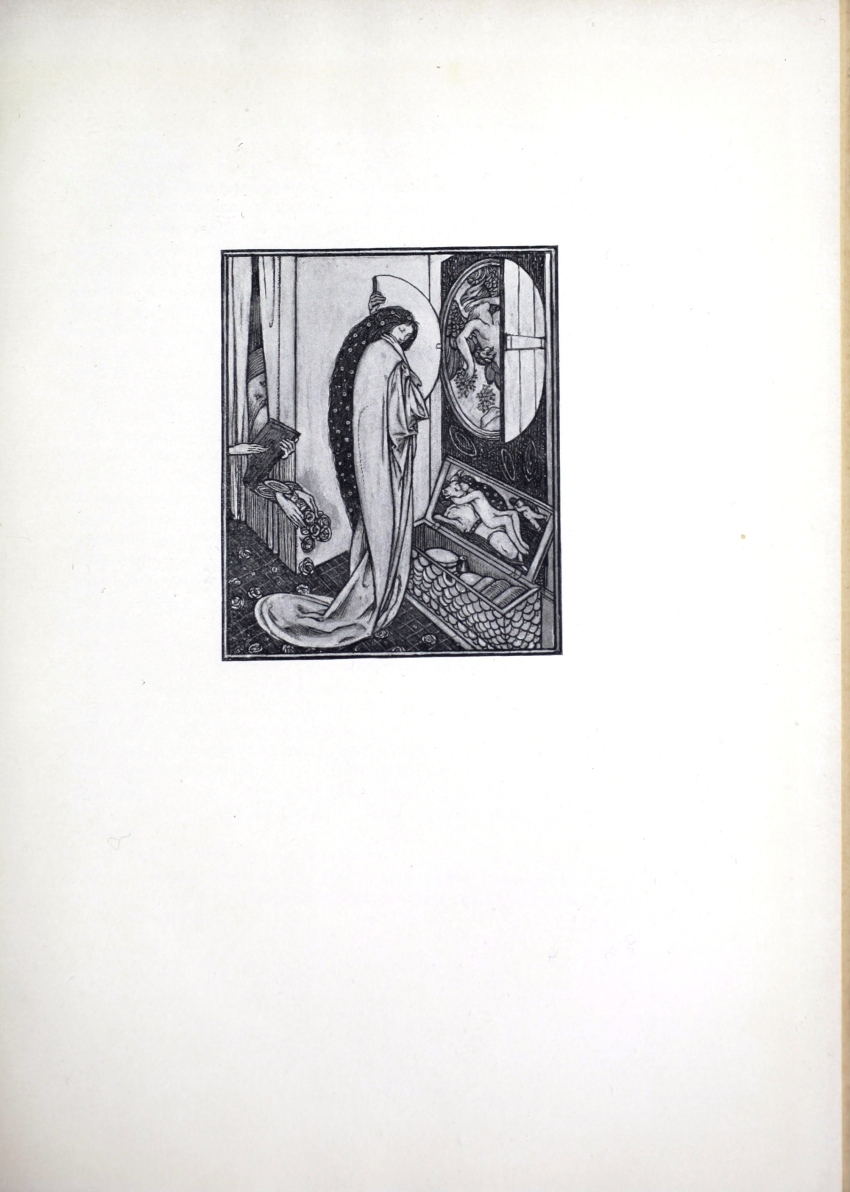

“Psyche in the House” by Charles Ricketts, The Pageant, 1896. p. 53

It seems incredibility appropriate then, that I will present my critique of The Pageant at NAVSA’s supernumerary conference in Florence, Italy this May. At that conference, I will offer a more detailed introduction to The Pageant and place it into conversation with four essays featured in its contents: J. W. Gleeson White’s “The Work of Charles Ricketts, Alfred J. Pollard’s “Florentine Rappresentazioni and their Pictures,” D. S. MacColl’s “Giulo Campagnola” and Charles Ricketts’s “A Note on Original Wood Engraving.” I want to focus on these essays because they place Ricketts’ book designs into both historical and international context. Through these works, we not only get a sense of Ricketts’ contributions to book history in Britain, but also of how the influence that Early Modern Italian illustrators, bookmakers, and publishers helped to differentiate the Aesthetes from the nationalist interests of their Pre-Raphaelite predecessors.

Like The Pageant, British Aestheticism often feels like a niche subject relatively unfamiliar even to Victorianists who do not study the movement’s artists. It’s most famous contributor, Oscar Wilde, was in prison by the time that The Pageant debuted. I would argue that the periodical’s focus on cosmopolitanism at that time is not a coincidence. Rather, condemnations of Wilde’s homosexuality and Aestheticism’s association with his supposed sins influenced the direction that Ricketts, Shannon, and White took the periodical in an attempt to strengthen British Aestheticism’s cultural cache at that dangerous time. By historicizing the movement and bringing attention to Ricketts’ Renaissance influences, The Pageant serves as a comment on the philistinism that condemned Wilde and Aestheticism. It accomplishes that feat by demanding that readers also connect Aestheticism’s controversies to the broader history of literature, of art, and of print culture. Rather than distancing itself from Wilde’s controversy, Ricketts’ work as a book designer becomes a means of redeeming their condemned friend and the movement he helped to make famous.

“Oedipus after a pen drawing” by Charles Ricketts, The Pageant, 1896, p. 65.